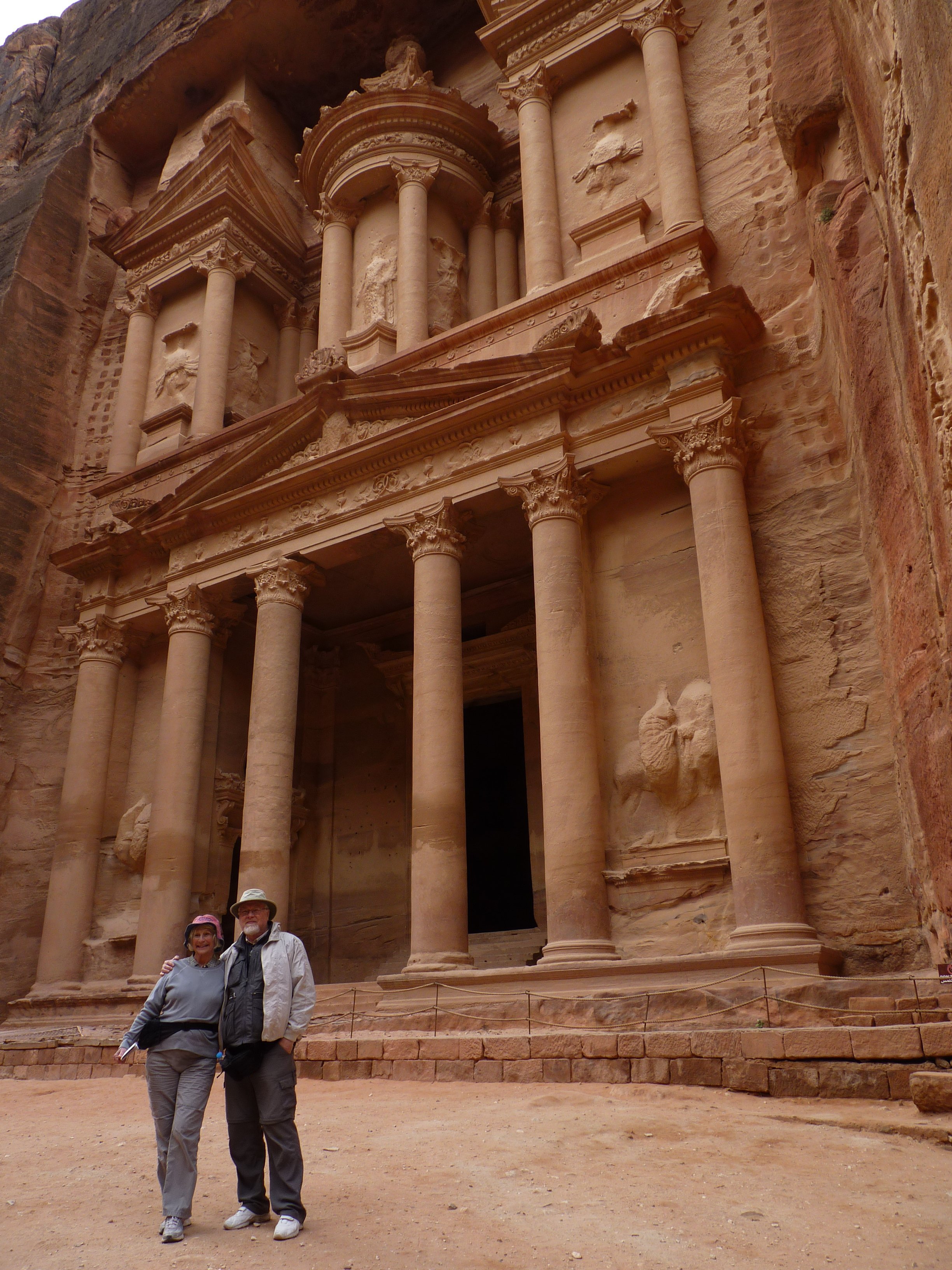

Diane and I love to travel, especially to other countries. Ever since we were volunteers in the Peace Corps to Chile beginning in 1966, we have traveled to many places, including many countries and territories within the following regions: South America, the Caribbean, Central America, Mexico, Europe, East Asia, Southeast Asia, Polynesia, Middle East, and North America. In fact, we have been in over 70 countries.

We began our travels abroad in 1966 as Peace Corps Volunteers (PCVs) in Santiago, Chile, where we lived from August 1966 until December 1968. After leaving Chile and traveling for another four months, with many stops in Peru, Brazil, and Trinidad and Tobago, we finally arrived home to Minnesota in April, 1969. In the following pages, Diane and I write about our many Peace Corps Volunteer-related adventures from the late 1960s, or what I refer to as our formative years as grownups.

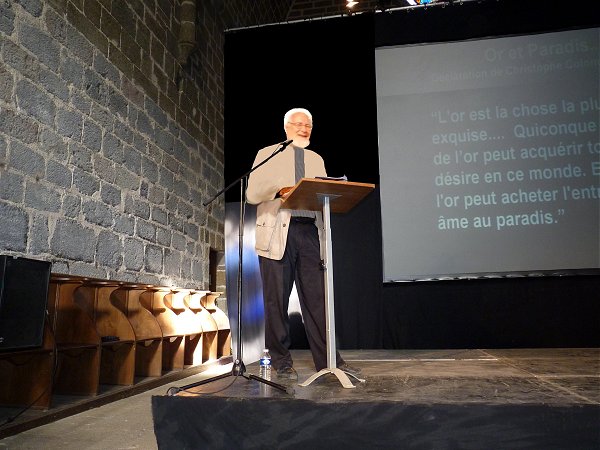

I (Dale) first began this section of my personal web page, which I title “Travel Tales and Snapshots,” in 2013 with small essays about and digital photographs from various cruises and other travels from that year to the present. These short stories are constantly being updated. Additionally, I am in the early stages of writing stories about earlier travels. Fortunately, in our current process of “down sizing” I came across some itineraries and other documents that help to refresh my memory, such as research field notes and letters written to our parents, which they saved. I begin by simply entering in the data from those sources, and later I try to turn them into interesting stories. These data trigger our memories, lead us to have many discussions about the past, and inspire me to write “travel tales.” I also have taken thousands of photographs, mostly slides and digital pictures, and many of them are included in these pages as “travel snapshots.”

Travels in 1966-1968

Puerto Rico: Peace Corps Volunteer (PCV) Language Training

June – August, 1966.

Diane and I were accepted into Peace Corps Volunteer (PVC) training in the spring of 1966. We were married on June 1965, a year after Diane graduated with BA and BS degrees in English and Spanish at the University of Minnesota, and soon after I finished my MA degree in music (Musicology and Flute Performance) at the University of Minnesota. Therefore, our Peace Corps training period was almost like a second honeymoon. We spent our first months of training at the University of Washington where we had a wonderful time at the beautiful “U-dub” campus in the Lake Washington area of greater Seattle. We visited the Cascade Mountains, saw Mount Rainier every day, visited Seattle’s highlights, cruised on Puget Sound, crossed over to Victoria, Canada, and had many other new experiences for us, including receiving about every vaccination and shot that existed at that time.

After completing our initial training in Washington state, we went for several weeks to Puerto Rico for advanced language training. There we had to find our own housing near the University of Puerto Rico (UPR) in Rio Piedras, and we soon found room and board with a wonderful family, which enabled us to improve our Spajjnish speaking skills. Being at the University of Puerto Rico gave us an opportunity to meet and interact with Spanish-speaking faculty members, which was important because our program in the Peace Corps was University Education and were all going to be teachers in Chile.

test

Insert letter from Diane, August 19, 1966

Insert letter by dale to parent on 9-11-66

Insert letter by Diane Sept. 7, 1966 “Yesterday I met the lady here …”

Insert same letter beginning “Dale has a nice set-up at the Conservatory of Music…”

Diane and I took several excursions with fellow Peace Corps trainees and occasionally UPR faculty members, visiting El Yugue rainforest, Luquillo Beach, and Old San Juan. Walking the streets of Rio Piedras was memorable, because we would hear coquis (tiny frogs) but could never see them; we have never forgotten their loud calls — “koKEE, koKEE.”

After several months we flew back home to Minnesota, then to New York City for our long flight to Chile. We finally arrived in Santiago as bonafide PCVs.

Santiago, Chile (and beyond): Peace Corps Volunteers

June 1966 – December 1968

Diane and I lived in Santiago, Chile, where we worked as Peace Corp Volunteers in group “Chile 19, University Education,” from early September 1966 through mid December 1968. Before our arrival to Santiago on September 15, we knew the city and name of the university where we would teach, but we did not know exactly what we would teach beyond our general discipline — “music” for me at the University of Chile and “English” for Diane at the Catholic University .

Background information about Dale’s musical experiences in Santiago

Dale’s Original Peace Corps Assignment — Recorder Instructor, University of Chile

I was assigned to the University of Chile, Facultad de Artes y Ciencias Musicales, which is a very fancy title meaning “Department of Musical Arts and Sciences,” or simply “Performance and Musicology.” This sounded good to me, but there were no details provided, and the University was on strike. A few days after our arrival to Santiago, I met with my Chilean host, Dr. Domingo Santa Cruz, the Music Dean of the University of Chile and Chile’s most famous composer. He told me I would be teaching recorder (flauta dulce in Spanish) to individual children after their regular school hours. The program in the University of Chile was called “Extension Musical,” — and it was basically musical instruction for children after school during the late afternoons and/or evenings. This sounded terrible to me! First of all, I wanted to teach during the day so Diane and I could have similar schedules. Secondly, I didn’t want to teach children who probably didn’t want to be in night school anyway. Thirdly, I did not know how to play recorder! Nevertheless, this was my official assignment, so I purchased an inexpensive soprano recorder in a Santiago music shop and in a week I became an expert because of my flute background. In a few weeks when school began, my second fear became true — my small handful of adolescent recorder students did not want to be there, did not practice, and often did not show up for their lessons.

Dale’s Self-Assigned Peace Corps Assignment — Principal Flutist, Philharmonic Orchestra of Chile

An Unorthodox Audition

During those first few weeks in Santiago I became good friends with Juan Bravo, the University’s flute professor and principal flutist with the Chilean Symphony Orchestra (Orquesta Sinfónica de Chile). He said “Dale, there’s an opening in the Philharmonic Orchestra of Chile (Orquesta Filarmónica de Chile) for principal flute. Auditions are next Wednesday, November 23 (1966), and you should go try out.” I did not realize that Santiago has two professional symphony orchestras, the “Symphonic Orchestra” and the “Philharmonic Orchestra,” funded respectively by the University of Chile and the municipal government of Santiago.

I was overjoyed with this opportunity to audition and possibly play principal flute in a professional orchestra. This was my life’s dream as a young flutist. For the next few days I practiced everything in my several music books of flute orchestral excerpts. Wednesday morning I left early to appear at 9:00 at the beautiful Municipal Theater in downtown Santiago. When I  arrived, however, the front door into the ornate foyer was open but nobody was around. I took our my flute and began playing several of the orchestral excerpts I had memorized — I was enjoying the wonderful acoustics in the foyer, and I suspected that my flute music was resounding throughout the concert hall. I was not aware of the orchestra slowly arriving onstage to begin its rehearsal. Suddenly, a bearded man in a suit and tie entered the foyer and said to me in Spanish [my translations follow], “Who are you? What are you doing here? You’re making a lot of noise and we are about to begin our orchestra rehearsal!” I replied, “I’m here for the audition for the principal flute position!” He responded, “The auditions were yesterday! But, can you start tomorrow?” Here I was, auditioning without knowing it, and getting my dream job, but not realizing it. The fact of the matter was, as I found out later, that none of the Chilean flutists that auditioned yesterday was good enough to be hired. My calendrical error was a godsend for me, not only because I was hired on the spot, but also because a primary rule of the Peace Corps is that Volunteers are not allowed to take jobs away from citizens of the host country. I explained who I was, and that I would be honored to become a member of the orchestra. I also explained that as a Peace Corps Volunteer, I could not accept a salary. However, we worked out an arrangement whereby the Orchestra gave me a stipend to pay for our housing and public transportation expenses. It was a deal that made both of us very happy.

arrived, however, the front door into the ornate foyer was open but nobody was around. I took our my flute and began playing several of the orchestral excerpts I had memorized — I was enjoying the wonderful acoustics in the foyer, and I suspected that my flute music was resounding throughout the concert hall. I was not aware of the orchestra slowly arriving onstage to begin its rehearsal. Suddenly, a bearded man in a suit and tie entered the foyer and said to me in Spanish [my translations follow], “Who are you? What are you doing here? You’re making a lot of noise and we are about to begin our orchestra rehearsal!” I replied, “I’m here for the audition for the principal flute position!” He responded, “The auditions were yesterday! But, can you start tomorrow?” Here I was, auditioning without knowing it, and getting my dream job, but not realizing it. The fact of the matter was, as I found out later, that none of the Chilean flutists that auditioned yesterday was good enough to be hired. My calendrical error was a godsend for me, not only because I was hired on the spot, but also because a primary rule of the Peace Corps is that Volunteers are not allowed to take jobs away from citizens of the host country. I explained who I was, and that I would be honored to become a member of the orchestra. I also explained that as a Peace Corps Volunteer, I could not accept a salary. However, we worked out an arrangement whereby the Orchestra gave me a stipend to pay for our housing and public transportation expenses. It was a deal that made both of us very happy.

(Letter by Dale to our parents, November 22, 1966). “I have some exciting news: you probably remember that we explained in an earlier letter that Santiago supports two symphony orchestras — the Sinfonia and the Filarmónica. Well, I am now the first flutist with the Philharmonic Orchestra of Chile. Both orchestras are about the same level — not as good as Minneapolis symphony, but very good, both doing major works. I will have rehearsals every morning from 10:00 to 12:00 except Sunday, and two or more concerts each week. This week, for example, we play a concert Thursday evening, and also play for a ballet production Saturday evening. Additionally, the first hornest, clarinetist, of bassoonest of my orchestra and the first oboist of the Sinfonia have asked me to play in a woodwind quintet with them. So, it sounds like I’ll get a lot of playing experience. Also, this will give me a certain amount of prestige so I won’t be a Santiago nobody who is trying to teach in the conservatory at the University of Chile. I mention this only because it’s important in Santiago, especially within the University of Chile, to have a title in order to have the respect of the students.”

Philharmonic Orchestra Concert Venues

I was hired after the end of the 1966 official concert season, so many of my first concerts were not in the beautiful Teatro Municipal, but rather in other Santiago venues. My very first concert, for example, was in the Club de Union during the evening of November 25, the North American Thanksgiving holiday. Diane wrote the following description of the venue and the concert in a letter to her parents on December 1, 1966: “Man, what a place! The Club de Union is a private club on the Main Avenue (Alameda) in Santiago, and it is quite exclusive, full of tapestry rugs, huge furniture in the several small rooms, chandeliers, statues, huge paintings in golden frames, mirrors, etc. In the very center room, the main salon, the orchestra performed its concert. The building has four floors, including balconies overlooking the main salon. I was quietly sitting one balcony above, looking down upon the orchestra, pretending this was my house, and the concert had been arranged for my sister (who is playing a piano concerto). I thought it was an old mansion and I was trying to imagine what it was like. But then, I got talking to the manager (who found me on the third floor looking down, and told me that the third floor was for men only). He explained that the building was constructed 14 years ago as a club, not a house at all. So I continued listening, quite normally again, to the concert. The musicians all played very well, especially Dale, in my prejudiced opinion. He has a good sound, and blends well. All solo parts he had sounded beautiful, especially in the Debussy piece.”

“The second concert Dale played in was in the Municipal Theater, where most of his concerts will be. This is another beautiful building, with tiered balconies held up by angels, a domed ceiling with a picture on it, a big chandelier, red plush seats, and white and gold trimmings.”

Dale’s Philharmonic Orchestral Repertoires and Schedules

When I joined the Philharmonic Orchestra of Chile, I didn’t have a very good idea of its repertoire or conductors. Diane actually learned some information about that before I did, as I wrote in a letter to our parents in Minnesota: “Di let me in on some news today concerning the Orquesta Filarmónica (my orchestra); it happened she saw a tentative schedule of events, which I had no idea of, and apparently we (the orchestra) will be giving a Brahms festival and a Beethoven festival. We will have several guest conductors including several famous ones from Europe and Latin America. We will be performing La Bohème and four other operas in the spring. It all sounds very interesting, fun, and beneficial for me.”

Diane wrote a letter to her family in Saint Paul, Minnesota, on April 28, 1967, in which she mentioned some meaningful observations about my first seasonal performance with the Philharmonic Orchestra of Chile. Here is an excerpt from Diane’s letter: “Last night was Dale’s official debut with the orchestra in its 1967 season. It was a very good concert, and I find the orchestra surprisingly good (after often hearing it’s the second-best orchestra in this two-symphony-orchestra-city).  Anyway, a person could sit back and enjoy it. Dale played very well, and he told me afterwards that several people, including orchestra members, the president of the orchestra, and also the conductor, had congratulated him and complimented him on his beautiful sound. He had a nice solo in the last movement of the Fourth Symphony by Brahms. I was sitting as far away as you can get, in the fourth balcony [see the very top of this photograph],and it came through great! By the way, I was a bit disillusioned about the beautiful Municipal Theater he plays in after sitting in the 4th balcony — there are no chairs, only step-like things to sit on. Talk about physical discomfort!”

Anyway, a person could sit back and enjoy it. Dale played very well, and he told me afterwards that several people, including orchestra members, the president of the orchestra, and also the conductor, had congratulated him and complimented him on his beautiful sound. He had a nice solo in the last movement of the Fourth Symphony by Brahms. I was sitting as far away as you can get, in the fourth balcony [see the very top of this photograph],and it came through great! By the way, I was a bit disillusioned about the beautiful Municipal Theater he plays in after sitting in the 4th balcony — there are no chairs, only step-like things to sit on. Talk about physical discomfort!”

I (Dale) wrote a letter to my musical colleague and best-man for our wedding, Leland Tolo, on December 1, 1967, in which detailed some or the orchestra’s activities and my experiences. Here is an excerpt from that letter: “Right now the orchestra is in the middle of what is called the spring season, or the summer season — I don’t know when one ends and the other begins. It includes a few outdoor concerts, trips to other parts of Chile near Santiago, and concerts in the Municipal Theater. Last week we played some concerts including Mendelssohn’s Midsummer Night’s Dream and Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony. My flute solo in the scherzo of the Mendelssohn brought bravos from the orchestra members during rehearsal when I played it (I was lucky). This week we’ll be playing Borodin’s Prince Igor and Stravinsky’s Firebird Suite. I can tell now that it’s going to be very difficult to leave in another year, because i enjoy playing so much, and the other members are really great friends. A lot of the members have asked me if we’re going to stay in Chile after the Peace Corps, and Thursday the president of the orchestra asked me to stay for a few more years.” I held the position for two seasons, until the end of our Peace Corps tour in December 1968.

Some Memorable Performances with the Philharmonic Orchestra

Diane wrote the following in a letter home, May 12, 1968: “Last night Dale played for a performance of the ballet Swan Lake by Tschaikovsky, presented by the National Ballet Company of Finland. I went to the Municipal Theater and sat for a while in the orchestra pit behind the basses, but I could not see well. During intermission, an usher found me a third-row seat way over to the side — part of the stage was behind a pillar, but at least I could see the dancers feet. It was a good performance.

“Then yesterday afternoon, I went to the Saturday concert of the Philharmonic Orchestra — an Austrian guest pianist played the Brahms Piano Concerto No. 2. He is also giving a recital on Monday night and he just happens to be playing Ravel’s Ondine — the second movement of Gaspar de la Nuit. When I met him after the concert, I tried to talk him into playing the whole piece, but he said that he needed to do a lot of practicing, although he does know the whole composition. He is very nice man, and we (he, Dale, and I) all had ice cream together in one of the orchestral hangouts, a little restaurant about half a block from the theater. So I’ll have to go to that concert too.

“But as busy as I was with the concerts, Dale was of course three times as busy, starting out with a rehearsal in the morning, and then playing two performances. The past week has been full — extra rehearsals for the ballet. Tomorrow he starts at 10:00 a.m. but won’t get home until 1:00 a.m. — great time for supper! After the ballet last night, some friends of ours came backstage — then Friday night, I also went to another ballet, Romeo and Juliet. I really liked the performance. Now I think I’ve seen enough ballet, at least from the pit (the cheapest tickets cost 35 escudos).”

Dale’s Camaraderie with the Philharmonic Orchestra Members

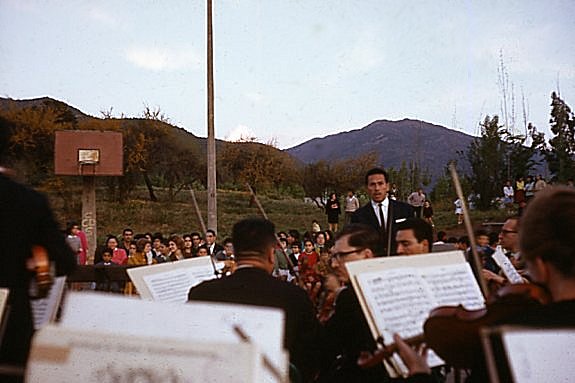

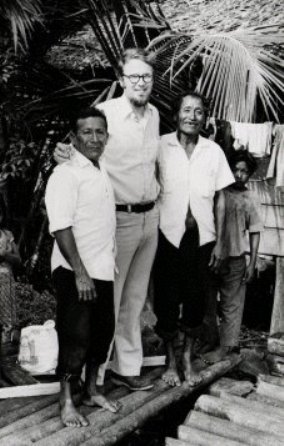

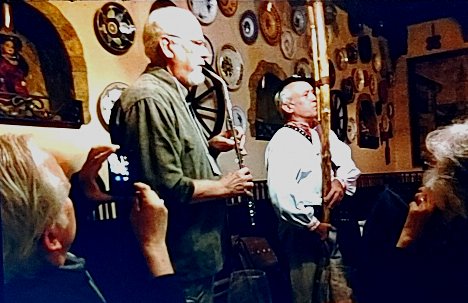

I made many very special friends in the orchestra, with plenty of joking.  Many times during rehearsals and just before I had a flute solo in some piece, the principal bassoonist would yell “dale que dale!” (my name, of course, but the phrase in Spanish means “go for it!” or “give it all you got” — from the verb dar, “to give”). I started out being called “gringo,” but soon became “gringito,” a big distinction meaning “friend” rather than “foreigner.” We had particularly good times during our orchestral tours outside of Santiago. This photograph was taken in Vina del Mar, on Chile’s coast, in December (summer in Chile), 1967, with me (the tall gringito) in the middle of the picture with a number of the orchestra’s wind players. Our orchestral tours were usually at the end of the season, in the Chilean spring or early summer (November). The following photographs give an idea of the venues, which were often outdoors.

Many times during rehearsals and just before I had a flute solo in some piece, the principal bassoonist would yell “dale que dale!” (my name, of course, but the phrase in Spanish means “go for it!” or “give it all you got” — from the verb dar, “to give”). I started out being called “gringo,” but soon became “gringito,” a big distinction meaning “friend” rather than “foreigner.” We had particularly good times during our orchestral tours outside of Santiago. This photograph was taken in Vina del Mar, on Chile’s coast, in December (summer in Chile), 1967, with me (the tall gringito) in the middle of the picture with a number of the orchestra’s wind players. Our orchestral tours were usually at the end of the season, in the Chilean spring or early summer (November). The following photographs give an idea of the venues, which were often outdoors.

Near the end of my final season with the Philharmonic Orchestra, the wind players held a farewell party for me at a local restaurant one evening. They had rented a small banquet room in the restaurant, and I remember that several long tables were placed end-to-end, covered with white table cloths, nice dinnerware, and a bottle of wine lined up in the center of the tables, as if there was one bottle per person. I don’t remember counting, but everything made for a wonderful and memorable time. The highlight of the party was after the meal when the principal trumpet player climbed up on his chair and sang the “Star Bangled Banner” in perfect English as a tribute to me. That wonderful endeavor still brings tears to my eyes every time I think about it, especially about the friendships I made with all of the orchestra members during those two years.

“The Woodwind Quintet “Arión”

I also became a member of a woodwind quintet made up of the principal wind players in the orchestra. We named our ensemble El Quinteto Arión, and we presented concerts around Santiago, in salons, small concert halls, schools, and other venues.  From left to right in this picture are Dale Olsen, flute; Sebastian Acuña, clarinet; Jorge Espinoza, bassoon; Jorge Maltrain, french horn; and Osvaldo Molina, oboe (principal oboist in the Orquesta Symphonica de Chile, i.e., the Chilean Symphony Orchestra).

From left to right in this picture are Dale Olsen, flute; Sebastian Acuña, clarinet; Jorge Espinoza, bassoon; Jorge Maltrain, french horn; and Osvaldo Molina, oboe (principal oboist in the Orquesta Symphonica de Chile, i.e., the Chilean Symphony Orchestra).

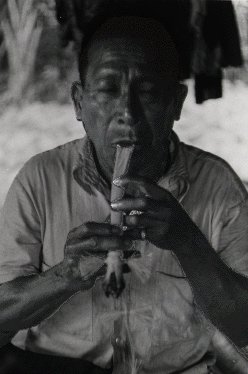

Ethnomusicologist with the Chilean Department of Popular Promotion

(Letter by Dale to Diane’s parents, 7.4.68) “Diane hasn’t told you about my new job (I have three jobs now), which used to be Peace Corps Anita’s job until she left Chile. I’m working with a Chilean governmental department called Departamento de Promocion Popular (Department of Popular Promotion), which has a several Chilean folklorists on its staff, working with rural Chilean folklore and music. These fellows, who are folklorists and not trained musicians, go into the remote areas of the Chilean countryside and record the folk music as sung and performed by old peasants (campesinos) in the hills. My job is to transcribe the music from their field recorded tapes into a guitar tablature musical notation. Then, some Chilean musician/teachers will teach those songs to Chilean children in the public schools. The purpose of this project is to save, preserve, and teach old traditional Chilean music so it will not become extinct. It’s great work for an ethnomusicologist, and it is my first contact with this type of folk music and my first experience transcribing it. I like the job very much — it’s challenging and ethnomusicologically very rewarding.”

Diane’s Original Peace Corps Assignment — Professor of English Language Literature, Catholic University of Chile

I (Diane) worked as a professor of English Language Literature at the Universidad Catolica de Chile (Catholic University of Chile), only several blocks from the Municipal Theater where Dale rehearsed and performed the Philharmonic Orchestra . My supervisor was Sister Cyria, a nun from Ohio. Dale and I became very good friends with her, giving flute/piano recitals for the students, going on countryside retreats with the nuns and other teachers, and being treated as colleagues. But it was teaching American literature that occupied most of my time.

Catholic University of Chile

(Excerpts from Diane’s letter to several college and church friends in Minnesota, November 5, 1967): School for me is drawing to a close — November 17 is the last day of classes. I’ve sure learned a lot and have enjoyed it. The students are just great — really friendly. In some of the other Chilean universities, the students have protested having Peace Corps Volunteers because they think we are spies. But the Catholic University here in Santiago is conservative in that respect (thank goodness). The Modern American Fiction course has gone pretty well — we’ve read several short stories. In the last unit we did titled individual, family, society, I got out of some work by assigning various students to teach the different stories. They did nice work! The last novel we are reading is To Kill a Mockingbird. The students are working on a term paper based on an American novel; I’ve been helping them individually with their outlines so they will write something readable.”

Daily Activities

(June 2, 1968, Diane’s letter home) “I am in a very bad mood tonight, so if it shows through the letter, just ignore it. My mood has to do with the fact that after many hours of work this weekend for one of my classes, they didn’t have the patience to wait 10 minutes, and left because I was late ( coming from another class (. This class has already missed a lot because of meetings, Welcome week, etc. I am tired of it, and will probably get mad at them when I see them wednesday. It may be a cross-cultural thing, each misunderstanding the other, but I don’t care. Sometimes Chileans seem to lack respect, but again, maybe that’s a North American interpretation — just to be fair.

“Last Wednesday was Phil Brink’s (Phil and Margaret Brink are new Peace Corps Volunteer musicians) trombone recital, with Dale and I playing a flute and piano piece in the middle of the concert. The Hootenanny group did some jazz and blues things for the second half. Afterwards we all came over here to eat something and rehearse after the performance. But Thursday we made a quick trip to Valparaiso to be on TV. The show was at 11:10 PM — we took a taxi back to Santiago afterwards, and got back about 2:00 AM. Dale couldn’t go along though, poor kid. He was planning to miss a couple concerts in the Philharmonic Orchestra’s Beethoven series, because there are only two flutes. However, the visiting conductor from Leipzig, East Germany, Herbert Kegel, who was also here last week, asked where the first flutist is, the American. So, the president of the orchestra contacted Dale, and he ended up playing Thursday night’s concert after all. This week we are supposed to rehearse at 10:30 PM Wednesday through Friday nights to prepare for a video-taped TV show. I’m not too excited about all these rehearsals, especially when I have so many papers to correct and lesson plans to work on. Sometimes I wish the days were a few hours longe; but, whenever I try to steal a few hours at night, I end up sleeping late the next morning. We have a French test Thursday, all oral! Oh well, at least we have our electric blankets.

We went to see up the down staircase, translated by the way is something something . . . ” END or CONTINUE WITH LETTER

House hunting in Santiago

Our First Housing Accommodations

When we arrived in Santiago on October 15, 1966, we were assigned to a downtown hotel for four days. We had to find more suitable housing on our own, although we were given suggestions for a temporary pensión or rooming house, which included breakfast. We found a comfortable place in downtown Santiago, where other volunteers were staying. Diane wrote the following in a letter home (October19,1966): “We have now moved out of the hotel into a pensión, which is like a boarding house with rooms for rent. Most of the people here are Peace Corps Volunteers — they joke about how the landlady is supported by Peace Corps because when volunteers come to Santiago, they almost always stay here. It is very cheap and comfortable for a temporary housing. It is an old house, with tall ceilings and doors. Compared to some of the other places we looked at, this is really nice and clean.”

It was in that rooming house where I (Dale) practiced my newly-purchased soprano recorder, which perhaps somehow led to an invitation for three of us PCVs to have lunch with a gentleman who wanted to talk to several young Americans. We don’t remember any of the details of that invitation, but we do remember the lunch because of the food. Although it was very tasty, as newcomers to Chile we recalled all the warnings we had during training about what foods not to eat. One rule was not to eat anything raw, such as lettuce (everything should be cooked for at least 15 minutes). Well, the first course was a salad with tomatoes and fish (we don’t remember if it included lettuce. The main dish was chicken and rice — very tasty! We were particularly warned during our training not to eat fresh strawberries or whipped cream. Wouldn’t you know that our dessert included fresh strawberries with whipped cream! “We really lucked out this time,” the other PCV exclaimed. We decided that, to be polite, only one of us should claim to be allergic to strawberries, and only another could claim to be lactose intolerant and cannot eat dairy products. Of the three PCVs, I think I chose to eat them both. Thankfully, none of us became sick. We figured that the warning probably did not pertain to Santiago, a modern city (in some ways, at least).

Diane explained the pensión’s shower in this interesting excerpt from a letter home (October 19, 1966): “I should tell you about this crazy shower I tried to take. For some reason we thought we did not have hot water in the pensión, so we bought a hot plate and a kettle, thinking we were pretty smart. But that thinking didn’t last very long — we blew a fuse the first time, and only time, we used it. We could hear a lot of commotion around the place, and I don’t know how many rooms were affected. We decided not to try that again. Anyway, the landlady told us that there was a shower down the hall that we could use. Well, that was confusing! Never saw such a contraption before! We lit a strange-looking water heater above the tub, and then I turned on the shower. What a capricious thing! First, pure cold water comes out. Then pure hot water, but not in a steady stream — it kind of spurts. And then, just steam pours out. It was really too funny — I was laughing so hard. I didn’t try to wash my hair like I had planned. Instead, I just had it done the next day at a little shop on the corner, by two girls with three dryers. It was a nice job, too, and cost only about six escudos or $1.20.”

House Hunting

Letter from Diane to her parents, December 1, 1966. “For a few days at the beginning of the week I had a horrible headache and stayed in bed. I’m fine now, though. Part of it was the exhaustion of looking in earnest for a place to live, since we’ve told the rooming house owner that we are leaving by the 9th of December ?? October. Looking in earnest means getting up at 6:30 AM, buying a paper at 7:00, arriving at a place at 7:30 or 7:45, and getting the people out of bed. We are finally catching on to some Chileno tricks, though. When it says you can see the place at 10:00, you arrive at 9:00. And even if you are the first person it’s no guarantee that you will get the place. The landlords love the position of power they have. They seem to delight in half promising 20 people the same place. But our courage continues. We have a strong possibility going for us tomorrow, we will see. At least we don’t have other things to do like lesson plans, shopping, or cooking.”

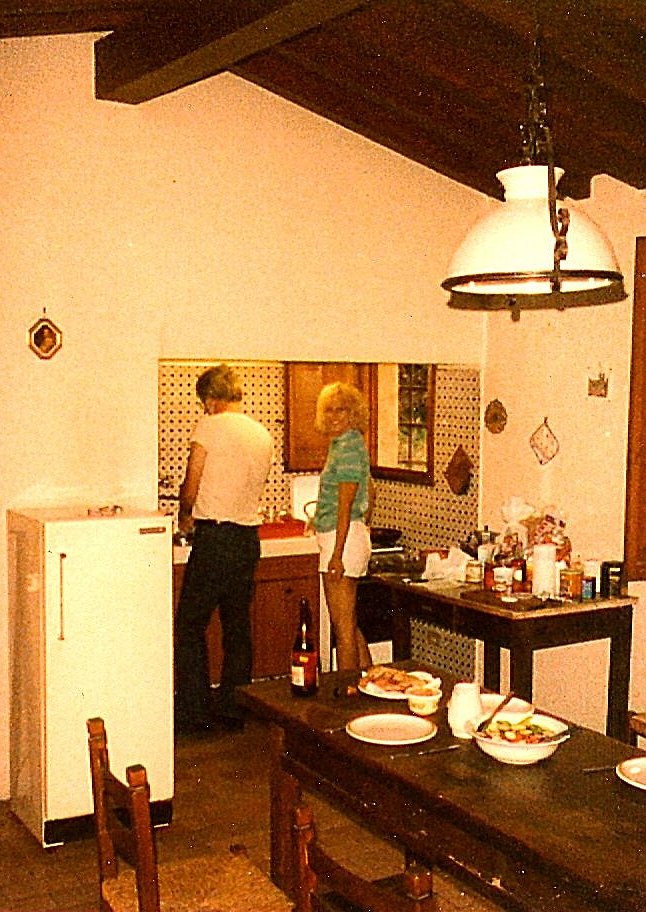

Our House in Santiago

(Letter from Dale to Diane’s parents, December 4, 1966). “It’s Sunday the 4th of December today, and we have a home, finally! We got up at 6:30 this morning and walked to the Alameda (the main street in Santiago) where we waited for the newsstands to open. After waiting for a half an hour and still nothing opening (they usually open at 7:00), we took off walking for the main part of town where we saw a man reading today’s newspaper. I asked him where he got it, and he sold it to us. Very lucky, too, because we couldn’t find anything open (we figured out that this man must have been our guardian angel).  We came across an ad for an apartment quite a ways east, toward the mountains, for 200 escudos ($40). So we hopped on a bus and got there about 8:00, and what a beautiful area — trees and more trees, with the mountains very close and looming in the background, completely covered with snow (it rained in Santiago last night, and when it rains here it snows in the mountains). The apartment is a separate little house built originally for the maid; it is in the backyard patio of the main house,

We came across an ad for an apartment quite a ways east, toward the mountains, for 200 escudos ($40). So we hopped on a bus and got there about 8:00, and what a beautiful area — trees and more trees, with the mountains very close and looming in the background, completely covered with snow (it rained in Santiago last night, and when it rains here it snows in the mountains). The apartment is a separate little house built originally for the maid; it is in the backyard patio of the main house,  behind and looming over the garage. It is two stories with a kitchen (complete with a sink, stove, and pantry), a living/dining room, and closet downstairs; upstairs is a bedroom, a smaller room with many windows, a closet, and bathroom with hot water and shower.

behind and looming over the garage. It is two stories with a kitchen (complete with a sink, stove, and pantry), a living/dining room, and closet downstairs; upstairs is a bedroom, a smaller room with many windows, a closet, and bathroom with hot water and shower.

The bedroom has two big windows that give us a nice view of the Andes. It will take a little work to make it nicer. For example, we’re going to paint the inside a color we like, I’m going to build some shelves, we have to buy furniture, a bed, table, etc. We get $600 from the Peace Corps for this, and are saving $100 a month from what most other people are paying, so we can afford a few decent things.

The bedroom has two big windows that give us a nice view of the Andes. It will take a little work to make it nicer. For example, we’re going to paint the inside a color we like, I’m going to build some shelves, we have to buy furniture, a bed, table, etc. We get $600 from the Peace Corps for this, and are saving $100 a month from what most other people are paying, so we can afford a few decent things.

“The apartment is quite a distance from downtown, but only two blocks from a street where buses and vans run almost every 5 minutes (bus service is very good here because very few people have cars) and they go within two blocks from where we work. It is such a beautiful area that it is worth the trouble of taking a bus.

“Mr. and Mrs. Blummel, the landlords/owners that live in a big house, are nice. Mr. Blummel is of German descent (he rattled off some German to me, but I couldn’t understand that at all); their older son is a medical student. We got on the subject of Communism and the Peace Corps, and they said at once that Communism is bad and that they are Christian Democrats (their political party).

“Not over 15 minutes after we had arrived, a fellow came in to look at the apartment and wanted it, but too bad, fella! About 15 minutes after that, while we were talking, a lady came to see it. Santiago is swarming with people who want apartments, and it’s still hard to believe we got such a good one for so little money.”

Buying Furniture in Santiago

bla

Parties at our House

bla

Other Activities Pursued during “Free” Time

What I (Dale) mean by “free” time is just about anything not related to our professional work as Peace Corps Volunteers. These include looking for housing, fixing up our house, buying furniture, church activities, giving and going to parties, attending concerts other than those of the Philharmonic Orchestra, going to movies, eating out, exploring Santiago and adjacent areas, other weekend traveling within Chile, and more. Lengthy and pre-prepared travels, either within Chile (first year only) or in other countries (second year only) are called “vacations,” and they are discussed under separate headings. Many of our “free” time activities are discussed chronologically when it is convenient to do so.

Exploring Santiago and Environs

During the first several months of our approximate 27 months in Chile, we enjoyed riding local busses to the ends of their routes. Often we would end up somewhere on a western slope of the mountains, where we would just walk in the the prestine foothills of the Andes. Most often there were no fences, no houses, and no commercial buildings — just a bus stop.  Busses usually arrived and left their final, end-of-the-line bus stop every hour, and if we had the time, we would leisurely hike and enjoy the beauty of nature, as Diane is doing in this picture — she’s picking wild flowers. Sometimes we would just stay on the bus and go back to where we first got on.

Busses usually arrived and left their final, end-of-the-line bus stop every hour, and if we had the time, we would leisurely hike and enjoy the beauty of nature, as Diane is doing in this picture — she’s picking wild flowers. Sometimes we would just stay on the bus and go back to where we first got on.

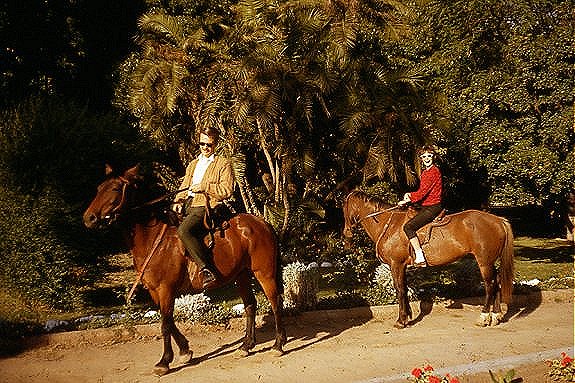

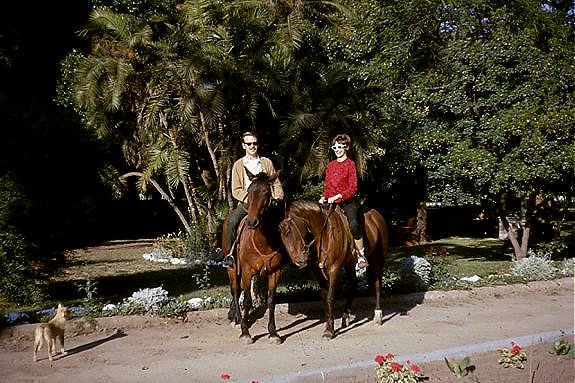

On one particular weekend, Sister Cyria, Diane’s superviser at the Catholic University invited us to go with her for a day to their Catholic nunnary or farm located several miles out of Santiago in Chile’s central valley. There we enjoyed their beautiful flowers and landscaping, including lovely patches of Birds of Paradise and other exotic (to us) flowers.

The highlight of that excursion with Sister Cyria, however, was the opportunity to ride several of their horses, which Diane especially enjoys. She is actually a very accomplished rider, and Dale, on the other hand, has never enjoyed the activity. Nevertheless, I (Dale) think we both look quite dashing on our nice Catholic horses.

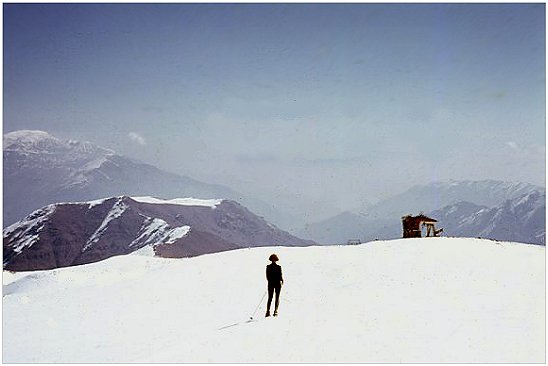

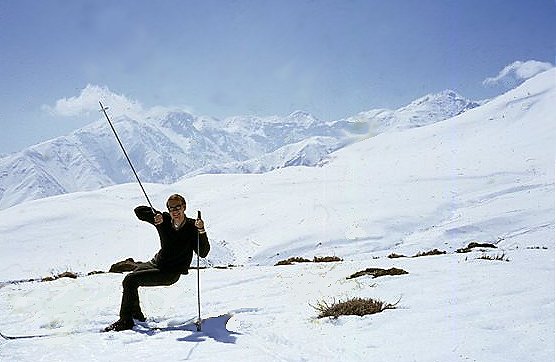

Skiing at Farellones, Chile (September 15, 1967)

Farellones is a ski facility with a hotel about 35 miles east of Santiago.  While it is close to the capital, compared to Portillo, for example, it is still in the rugged Andes, albeit at a middle elevation of the Andes mountains. It is a favorite weekend spot for many residents of Santiago because it is fairly close and easy to get to, it is cheaper than the famous Portillo ski resort near the Argentine border, and most of Farellones ski slopes are easy to manage for amateurs. Farellones skiing in September (springtime in Chile) is sweater skiing and the slopes were perfect for us because we had never really skied much before. Skiing in Minnesota was never enjoyable — it was always way too cold for humans, and there are only a few hills around the Twin Cities and they are always crowded. Therefore, we had fun in Farellones because it was like cross-country skiing without trees, with beautiful snow capped mountains in nearly every direction, and there were hardly any other skiers. We got a ride to the ski area with one of Diane’s students from the Catholic University.

While it is close to the capital, compared to Portillo, for example, it is still in the rugged Andes, albeit at a middle elevation of the Andes mountains. It is a favorite weekend spot for many residents of Santiago because it is fairly close and easy to get to, it is cheaper than the famous Portillo ski resort near the Argentine border, and most of Farellones ski slopes are easy to manage for amateurs. Farellones skiing in September (springtime in Chile) is sweater skiing and the slopes were perfect for us because we had never really skied much before. Skiing in Minnesota was never enjoyable — it was always way too cold for humans, and there are only a few hills around the Twin Cities and they are always crowded. Therefore, we had fun in Farellones because it was like cross-country skiing without trees, with beautiful snow capped mountains in nearly every direction, and there were hardly any other skiers. We got a ride to the ski area with one of Diane’s students from the Catholic University.  The following photographs are of us enjoying the snow and cross country skiing at this beautiful place in the Chilean Andes. Most of the time we would quietly glide along the gentle slopes, sometimes we would gently fall, and sometimes ham it up for a photograph — always with lots of smiles and laughter.

The following photographs are of us enjoying the snow and cross country skiing at this beautiful place in the Chilean Andes. Most of the time we would quietly glide along the gentle slopes, sometimes we would gently fall, and sometimes ham it up for a photograph — always with lots of smiles and laughter.

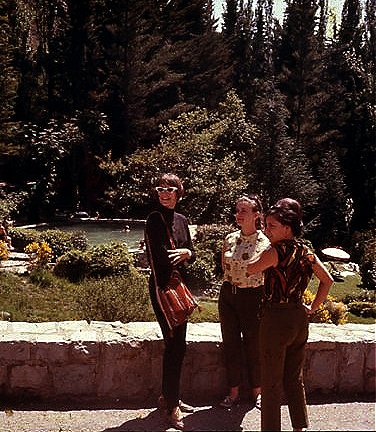

Later, on weekend in the fall of 1968, we spent a beautiful half day in Farellones with our newly-made PCV musician friends, Phil and Margaret Brink, seen with us in this photograph. They arrived in Santiago in the fall 1967 and left in 1969. We performed many concerts together with them, especially in a folk group that several us PCVs formed in 1967.

Later, on weekend in the fall of 1968, we spent a beautiful half day in Farellones with our newly-made PCV musician friends, Phil and Margaret Brink, seen with us in this photograph. They arrived in Santiago in the fall 1967 and left in 1969. We performed many concerts together with them, especially in a folk group that several us PCVs formed in 1967.

Church Activities

Finding a church home in Santiago during our 30 months living in Santiago was important to us. Shortly after we became settled in our house, after weeks of search for a suitable place, we visited the Santiago Union Church, Santiago’s only English-speaking church in the 1960s. We became very close friends with Rev. Toby Legg and his wife, who was the organist at the church. Months after first attending, we were invited to be the coordinators of the church’s youth group, which we accepted. MORE

“Next Thursday (which is some kind of holiday here ( the Methodist church has asked us to play for some big deal- – it’s Methodist week or something like that. I’m sure glad that we brought our one and only Gospel song book. I’ve been playing that crazy harmonium for the church on Sunday mornings, by the way.” (May 18, 1968 letter)

Peace Corps Volunteer “Hootenanny” Folksong Group

Our particular Chilean Peace Corps group, known as “Chile 19, University Education,” included a number of very fine amateur as well as professional musicians. I was the only professional symphonic and jazz musician in our Santiago contingent, but there were several other talented Peace Corps Volunteers in Santiago pertaining to other groups who were singers, guitarists, and banjo players, and one talented actor. In early 1967 many of these artists, including Diane, joined together and formed what they called the “Peace Corps Hootenanny” group, specializing in North American folksong performance.

These first two photos show the group in an outdoor performance in Santiago — Diane can be seen in the front row wearing white-rimmed dark glasses. Diane wrote the following interesting paragraph about a particular performance (April 28, 1967, letter home): “Last Saturday night our Hootenanny group took to the road again. This time we went a little south to the town of San Bernardo. One of our group lives in a población (“shanty town”) there, and made arrangements for our group to perform. There was quite a big crowd in attendance, but I think they were attracted mainly by the boxing matches which “sandwiched” us. Boxing isn’t a major sport here, and the boxers weren’t very good. It was a cold night, and the event took place outside. I can imagine the boxers were a little “chilly” (pun intended) in their boxing trunks. We’ve sung on some interesting stages, but this was something else — climbing up to the high stage and then having to crawl through the ropes of the boxing ring! The crowd sure enjoyed that!

These first two photos show the group in an outdoor performance in Santiago — Diane can be seen in the front row wearing white-rimmed dark glasses. Diane wrote the following interesting paragraph about a particular performance (April 28, 1967, letter home): “Last Saturday night our Hootenanny group took to the road again. This time we went a little south to the town of San Bernardo. One of our group lives in a población (“shanty town”) there, and made arrangements for our group to perform. There was quite a big crowd in attendance, but I think they were attracted mainly by the boxing matches which “sandwiched” us. Boxing isn’t a major sport here, and the boxers weren’t very good. It was a cold night, and the event took place outside. I can imagine the boxers were a little “chilly” (pun intended) in their boxing trunks. We’ve sung on some interesting stages, but this was something else — climbing up to the high stage and then having to crawl through the ropes of the boxing ring! The crowd sure enjoyed that!

I joined the group as a singer and jazz flutist during its second year. For two years the PCV Hootenanny Group performed for Peace Corp and Santiago events, and during the second year we also appeared many times on Chilean television, as seen in this black and white photo taken in the television studio. INSERT PHOTO HERE.

Diane wrote the following about one of our performances (letter from May 18, 1968): “Well, the big news is that we are TV stars now. Last Saturday was the first big television performance of our Hootenanny group. It was an interview type show with a big, rather obnoxious master of ceremonies. The show is made up of miscellaneous acts, and we were one of them. Between our songs, the Master of Ceremonies interviewed us, asking us what kinds of jobs we have here in Chile, why we are here, how the wages compare, etc. We sang three songs, including the one we do with Dale playing jazz flute.

“Considering the type of program it was, it is surprising how many people happened to see us. The next day for example, I went to a morning concert, and a lady said she saw me on TV; and at school the kids all commented about it.

“Then, Wednesday night we were on television again, in a different type program entirely, with better organization and planning. They aired pictures of New York during our music, with narration by Bruce, an African American Peace Corps Volunteer, who read a Spanish poem about New York by Garcia Lorca (he actually had it memorized — he’s in a drama group), and us. We sang only two numbers, and the rest were solos or other combinations. Dale, Pete (a guitarist), and Anita (a very good folk singer) performed Summertime by George gershwin, and it was very professional. We enjoyed the camera work and techniques of the TV crew, and it was really great to be a part of the show. The next day, however, we hardly talked to anyone that had seen it. One of the Peace Corps leaders forgot about it, and the other big wigs didn’t know about it. Even sister Cyria missed it, although she very much wanted to see us — she had to stay late at school. So, after doing such a good job (at least we were pleased), very few friends even saw us. Those who did, however, really liked it. Some Peace Corps Volunteer colleagues ran around looking for television sets that were turned on, but couldn’t find any.

“Next Friday, our Hootenany group has been invited to sing in Temuco, which is a 15-hour bus ride south of Santiago. Dale has a concert or rehearsal the next Saturday morning at 10:00 a.m., but the PC big chief, Paul Bell, said Peace Corps would pay for his flight back — thus, he may be able to go. Dale really adds class to the group.

Our first Snowfall in Santiago

Excerpts from Dale’s letter to Louis Paff, a college friend, June 7, 1967. “Cold weather is settling in. On June 5, about 6:30 in the morning, our landlords pounded on our door to wake us up. They were all excited about something. It had snowed here in Santiago overnight. They said that such a momentous event last occurred 20 years ago (i.e., 1947). The Chilenos just loved it. Schools were closed in the morning, although the snow only lasted until about 10:00 AM, if that long. Compared to our strong and hearty Minnesota snowfalls, this was nothing. However, it sure looked odd to see snow on the palm trees, and the Andes mountains to our east are now completely snow covered and so majestic. The snow in Santiago soon became very slushy, however, but the day is perfectly clear and sunny. The snowfall seemed to clean the air and remove the smog.”

Halloween Party In Santiago, October 31-November 1, 1967

Excerpts from Diane’s letter to her family, Nov. 6, 1967. “Last Sunday was completely shot. After church we went to Fernando (the 2nd flutist in the Philharmonic Orchestra) and Liliana’s house for lunch, and after that we went to a flower show at the United Nations building here in Santiago. Then we had to go home and get dressed for the Halloween party sponsored by the Santiago Union Church, organized by and for the church’s youth group, which we direct. Both Dale and I made elaborate masks out of paper mache (papier-mâché) — Dale made a huge monster head and I made a witch’s face mask and a hat (seen below in the following four pictures).

“The Blummels (our landlords) got a big kick out of all our work (we spent about two or three nights making our costumes), and they even helped with the finishing touches of paint. Dale’s head is purple, with big bulging bloodshot eyes. We hung them in our bedroom after we finished making them.

“The fun really began when we got dressed up for the party. Fernando transported us to the vicinity of Paul Bell’s house (Mr. Bell is the Peace Corps director in Chile, and a member of the Union Church), and we had to get out of the car and get “headed” up for our entrance, since Dale’s monster head wouldn’t fit in Fernando’s little car (in this photo Diane is helping Dale adjust his big monster head).  Because we did not want to arrive together, Dale took a quick jog around the block, followed by curious children (Chileans don’t dress up for Halloween). I took a different route and had my following, too. We both looked awful, meaning scary. The street kids called me la bruja fea (“the ugly witch”), of all things! When we got to Bell’s house, I must admit that we both felt a little disappointed because the young people of our youth group hardly did anything to disguise themselves. We fooled them for a while, but, by the process of elimination, we were identified. Paul Bell has a little son about 6 or 7, and it was so cute because he would walk up to Dale and offer his hand, just to be sure Dale was at least a friendly monster. And he was very much in awe of me. I’m sure he was disappointed when I took off my mask, however, because he certainly believed that he had a real witch in his back yard!

Because we did not want to arrive together, Dale took a quick jog around the block, followed by curious children (Chileans don’t dress up for Halloween). I took a different route and had my following, too. We both looked awful, meaning scary. The street kids called me la bruja fea (“the ugly witch”), of all things! When we got to Bell’s house, I must admit that we both felt a little disappointed because the young people of our youth group hardly did anything to disguise themselves. We fooled them for a while, but, by the process of elimination, we were identified. Paul Bell has a little son about 6 or 7, and it was so cute because he would walk up to Dale and offer his hand, just to be sure Dale was at least a friendly monster. And he was very much in awe of me. I’m sure he was disappointed when I took off my mask, however, because he certainly believed that he had a real witch in his back yard!

“During the party there were the traditional Halloween games and barbequed hamburgers. The kids from the youth group did all there own planning — some things went over well, and others not so well. I presume they learned something anyway. The youth ended by playing Charades and singing folksongs.”

A Scary Event in Santiago, December 1, 1967

Excerpts from Dale’s letter to Leland Tolo, a college friend: “Diane and I have been keeping busy, and so far have managed to survive the earthquakes, uprisings, fiestas, and even the riot on Thanksgiving day when five or so people were killed here in Santiago. The trouble was caused by a communist-inspired strike or stop during which many of the city’s workers walked off their jobs, including bus workers, city utility (gas, water, and electricity) workers, and people from about 25 other agencies and companies. Fortunately, we were out of town on a concert tour with the Chilean Philharmonic Orchestra. When coming back on the orchestra bus late at night, we saw army and police in many parts of Santiago with rifles, tanks, etc. I guess they had to use tear gas in a few areas of town to disperse the rioters. Unfortunately, there were deaths, including the death of an innocent 8 year old boy who was accidently shot.”

Travels Outside Santiago during the First Year of our Peace Corp Tenure

During our vacation times from our Peace Corps jobs, Diane and I traveled throughout much of Chile from its far north in the Atacama Desert to Puerto Mont in south/central Chile. We also visited Buenos Aires in northern Argentina, Ushuaia in the extreme south on the Beagle Canal, took a train across the pampas from Buenos Aires to Mendoza, hitchhiked across the Andes from Mendoza to Santiago, skied in Farellones and Portillo, and much more. Some of these trips out of Santiago and daily experiences in the city are written about below, as letters, field notes, diaries, or remembrances. They are presented here in chronological order, because during our first year, PCVs were not allowed to travel out of the host country — In fact, our US passports were safely stored in the Peace Corps office in Santiago.

Vacation to the Chilean Lake District: (1) Temuco, Llaima Volcano, Lake Conguillío in the La Araucanía Region, and (2) Osorno Volcano, Lake Llanquehue and Lake Todos los Santos (January 20-30, 1967)

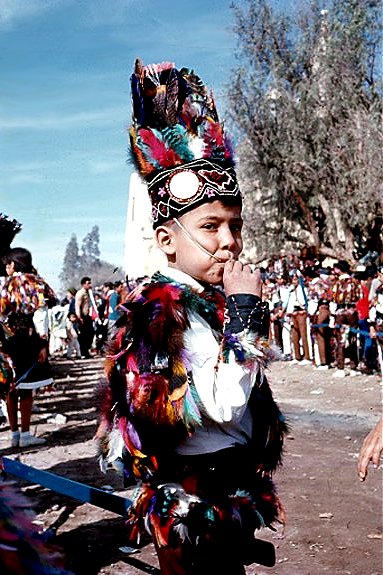

This was our first extended trip in Chile, which lasted ten days. The following is an excerpt from Dale’s letter to his parents written on January 23, 1967: “We’ve been taking our time (by train and hitchhiking) from Santiago to the central/south of Chile known as the lake district, seeing some of the most beautiful scenery we’ve ever seen. Arriving in Temuco, we visited a Peace Corps Volunteer (PCV) couple at their small cabin that they built themselves on an isolated hill with a perfect view of Mount Llaima, an active volcano. They work with the Chilean Mapuche Indians. From their house we drove north on a farm road with them, another PCV couple who work in forestry, and a Chilean couple, agrarian specialists who drove their vehicle. Soon the farm road ended and we continued driving on narrow winding path on a black lava field created by the large volcano. Before too long we reached Lago Verde from where the path continued into forests of Araucanian pines, bamboo groves, and moss-covered trees, with the snow capped Andes mountains ahead of us. We finally arrived at Lago Conguillío, our destination, and what a beautiful sight it was, with its crystal clear water, backdrop of snow capped mountains, and green forests — completely unexploited by tourism. There we fished, hiked, and ate our picnic lunch.”

Today, this beautiful area is known as Conguillío National Park, which includes ski-tows and ski-runs up and down the snow-capped Llaima Volcano. We were so fortunate to see it in a truly pristine state.

Our next destination was the town of Puerto Varas and Lake Llanquihue, followed by the Petrohue River, Osorno Volcano, and Lake Todo los Santos.

Vacation to Portillo and Christ of the Andes (April 15, 1967)

I wrote the following letter to our parents on April 5, 1967, explaining a little about our plans for a short vacation before our work schedules started: “This weekend we’re going to take a few more days of our vacation: we’re going to take a bus to Portillo and Christ of the Andes. The reason for this trip is because the son of our family, a third year medical student (a Christian Democrat) is going to have an all night party in the main house (we live in a small apartment behind the garage) with 70 of his medical student friends (most of them Communists).  He said his parents are going to sleep elsewhere and he advised the we do the same if we want to get any sleep. Although he did invite us to the party, we decided to go off somewhere rather than argue with Communists all night. We were also encouraged by an American friend who lives in Santiago to visit Christ of the Andes before winter.”

He said his parents are going to sleep elsewhere and he advised the we do the same if we want to get any sleep. Although he did invite us to the party, we decided to go off somewhere rather than argue with Communists all night. We were also encouraged by an American friend who lives in Santiago to visit Christ of the Andes before winter.”

Therefore, we began to prepare for our excursion, and one April weekend in the late Chilean fall we traveled by train high in the Andes with a Chilean friend to a military post where his brother was stationed, and from there we hitchhiked to Portillo, Chile’s best known ski area high in the Andes east of Santiago. From Portillo we hitched a ride further to Christ of the Andes (pictured here to the right), just across Uspallata Pass and the border with Argentina. We spent the night in a small village named Las Cuevas in Argentina, and we will never forget sitting outside our quest house in the very frigid air, looking up at the stars of the southern hemisphere — an unbelievable site. The next morning we got a ride to the statue of Christ of the Andes with an American man who worked with the United Nations.”

The huge statue, supposedly made from melted down cannons, sits upon its concrete bass at 12,572 feet (3832 meters) above sea level. It was created by the Argentine sculptor Mateo Alonso in Buenos Aires and transported piece by piece to its present location in 1904. The Spanish inscription at the base of the statue reads “Se desplomarán primero estas montañas antes que chilenos y argentinos rompan la paz jurada al pie del Cristo Redentor” (roughly translated, “May these mountains be torn asunder before Chile and Argentina ever break the peace treaty made at the feet of Christ the Redeemer”).

Travels Outside Santiago and Outside Chile during the Second Year of our Peace Corp Tenure

Vacation to Patagonia: 1) Punta Arenas and Torres de Paine in southern Chile, and 2) Ushuaia in Tierra del Fuego in southern Argentina (December 26, 1967-January 5, 1968)

During part of our summer vacation, between the day after Christmas 1967 and five days after New Year’s 1968, we traveled to Punta Arenas in the extreme south of Chile on the Strait of Magellan, then further south to Ushuaia in Argentina in Tierra del Fuego on the Beagle Canal. This period of time was in the middle of the summer in the southern hemisphere, when many of the Chileans in Santiago go on vacation.

Diane explained our modes of travel, distance covered, and many details of our adventures in a letter to her parents dated January 17, 1968. “I will begin with where we went and the approximate number of miles covered: (1) south by airplane from Santiago to Punta Arenas = 1400 miles; (2) north by automobile to Puerto Natales and Torres de Paine, then back to Punta arenas = 400 miles; (3) east and south by automobile to Ushuaia, Tierra del Fuego, Argentina = 300 miles; (4) north by airplane to Buenos Aires, Argentina = 1500 miles; (5) west by train to Mendoza, Argentina = 600 miles; (6) west by truck and automobile to Santiago = 250 miles, for a grand total of 4,450 miles in 2 weeks.

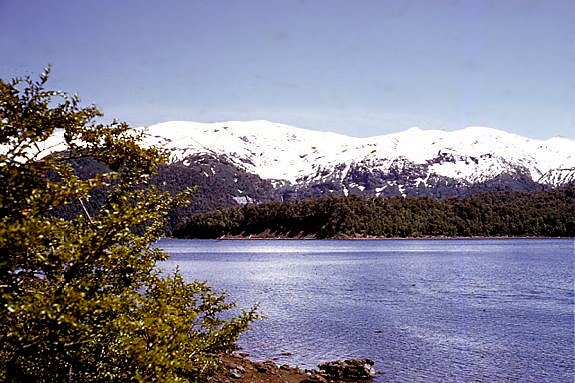

“Our flight to Punta Arenas was really beautiful. Luckily, we had a clear day, and our plane, a DC-4, didn’t fly as high as some of the bigger planes. South of Puerto Mont we saw many glaciers, some miles long, endless mountains, estuaries, fiords, and canals. If we would have had time, we would have liked to take a boat trip from Puerto Mont to Punta Arenas, but it’s a 5-day trip. As we flew over the mountain named San Valentin, near Puerto Aisen, it seemed really close to us, completely covered with snow, ice, and glaciers. Punta Arenas is a Chilean port city on the Strait of Magellan in a region known as southern Patagonia.”

Our Methodist minister in Santiago gave us a letter of introduction to the Methodist minister in Punta Arenas, an American missionary, and we were able to stay with him and his family for several days. We comfortably slept on two cots in our sleeping bags in the recreation room of their church. They were wonderful hosts, and Diane and I performed flute and piano music in their little church on Sunday morning.

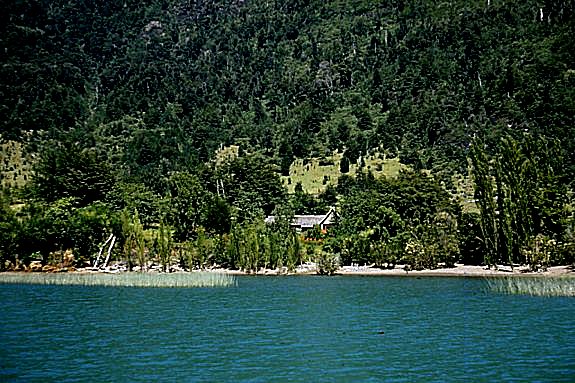

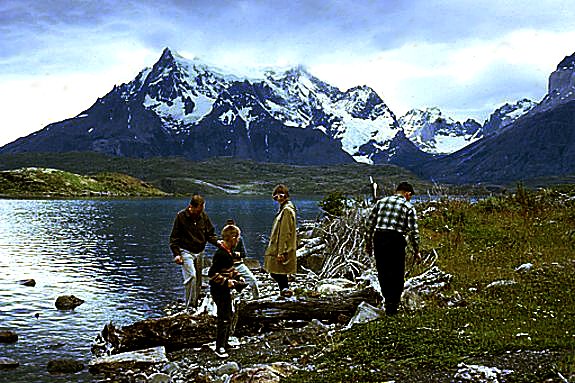

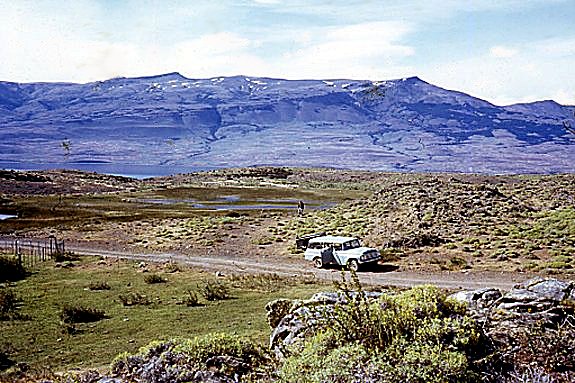

They invited us to go with them in their car (this photo) to the Patagonian mountain and lake region known as Torres de Paine (“Paine Towers” — paine means “blue” in the language of the Tehuelche native people of Patagonia) where they planned to gather rocks to build a fireplace for their house. We were delighted to go with them — it was a wonderful opportunity for us to visit that incredibly scenic, rugged, and pristine region in the high southern Andes, long before it became a popular tourist attraction, even though it was established as a national park in 1959. The Torres de Paine National Park is today one of the most sought out tourist destinations in the southern Chilean Patagonia, unfortunately replete with hotels and modern tourist facilities. In 1967, fortunately, there were absolutely no facilities — it was truly one of God’s unspoiled gardens.

Our trip began with a five-hour long drive to Puerto Natales, located on a Chilean estuary northwest of Punta Arenas. There we spent the night in our sleeping bags on the floor of a small church. The next day included a three-hour drive on a dirt road across a fairly flat part of the rugged Chilean Patagonia, as seen in these photographs. The only wildlife we saw was a lone guanaco (the southern Andean relative of the central-Andean llama and alpaca) in the middle of the road.

We finally arrived at the site where our missionary friend intended to collect rocks, along the shore of Lake Pehoé, a beautiful sight with the Cuernos de Paine in the background, across a crystal clear fresh water lake fed mainly by the Paine River.

While our friends were off gathering rocks, we were given the task of cooking dinner, which would consist of two mutton legs that we bought in Puerto Natales. The setting for the barbeque was unbelievably beautiful, and very windy and rather cold. This photo is a 1967 selfie of us posing on a hill with Cuernos del Paine (“Horns of Paine” and other particular mountain formations in the Torres de Paine region) in the background.  Our barbequing of the mutton was not a success because it was not tender. We were not told how to cook it, and I was relying my Minnesota Boy Scout cooking-over-a-fire training. We grilled it over my “musician’s” fire (pretty, hot, but inefficient for cooking), but the wind and lack of a cover over the meat caused the mutton legs to be tough. We were later told that we should have stewed it in a pot of water. Who was to know! We have forgotten how tough the meat was, but we will never forget this picture of us two cooks, with the beautiful background of the Torres de Paine. We were so fortunate to visit that outstandingly scenic, rugged, and unspoiled region in the high southern Andes of the Chilean Patagonia, long before it became a major tourist destination.

Our barbequing of the mutton was not a success because it was not tender. We were not told how to cook it, and I was relying my Minnesota Boy Scout cooking-over-a-fire training. We grilled it over my “musician’s” fire (pretty, hot, but inefficient for cooking), but the wind and lack of a cover over the meat caused the mutton legs to be tough. We were later told that we should have stewed it in a pot of water. Who was to know! We have forgotten how tough the meat was, but we will never forget this picture of us two cooks, with the beautiful background of the Torres de Paine. We were so fortunate to visit that outstandingly scenic, rugged, and unspoiled region in the high southern Andes of the Chilean Patagonia, long before it became a major tourist destination.

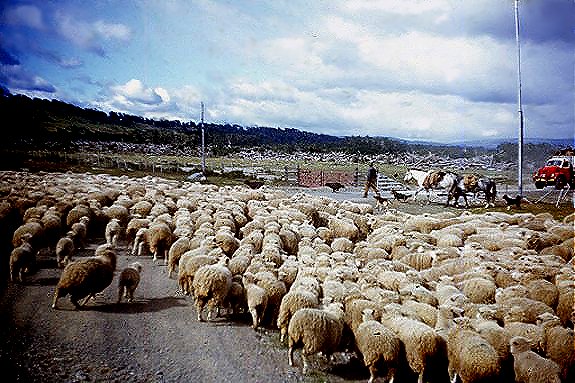

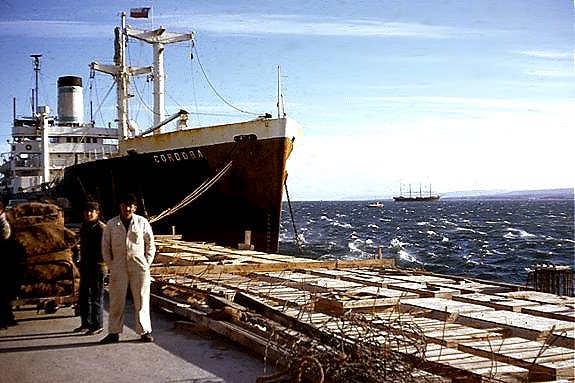

Back in Punta Arenas, a port city on the Strait of Magellan, its shipping docks are constantly busy, with many large and small freighters coming and going. The town is windy much of the time, and cold at night. It is a very flat along much of the shoreline — Punta Arenas means “sandy point” in Spanish) — and the trees are stunted and wind-blown. This region of southern Patagonia is known for sheep raising. Because Punta Arenas is a freeport, we spent time buying stuff we can’t get in Santiago, like Raisin Bran, Grape Nuts, Whip and Chill, coconuts, cleanser, a dessert mix, and candy. Fruit is expensive in Punta Arenas, and very few flowers grow here. The sheep, however, grow like crazy, and the hundreds of sheep, the herders with their horses and sheep dogs, often congest the main road into Punta Arenas during their often daily migrations.

The town is windy much of the time, and cold at night. It is a very flat along much of the shoreline — Punta Arenas means “sandy point” in Spanish) — and the trees are stunted and wind-blown. This region of southern Patagonia is known for sheep raising. Because Punta Arenas is a freeport, we spent time buying stuff we can’t get in Santiago, like Raisin Bran, Grape Nuts, Whip and Chill, coconuts, cleanser, a dessert mix, and candy. Fruit is expensive in Punta Arenas, and very few flowers grow here. The sheep, however, grow like crazy, and the hundreds of sheep, the herders with their horses and sheep dogs, often congest the main road into Punta Arenas during their often daily migrations.

After Punta Arenas we hitched a ride on a small freighter, crossing the Strait of Magellan to Porvenir, a tiny Chilean village on the north shore of Tierra del Fuego. We weren’t sure what to do when we walked into the ship’s hold with our stuff. Once the boat began its crossing, one of the sailors saw us huddled in the hold and invited us up on deck where were were offered coffee and food. We weren’t expecting such service, and we were trying to be invisible so as not to be charged for the trip. The crew, however, was very hospitable, and they were very happy to give us a lift.  When we arrived on land once again, on this huge island known as Tierra del Fuego, meaning “Land of Fire” (so named because of the many bonfires the Native Americans always had burning during the age of Spanish and Portuguese exploration when Ferdinand Magellan first sailed through the strait that now bears his name), we disembarked and I took the following photograph of Diane, the ship, and the calm waters of the strait. I call this photograph la inmigrante, “the female immigrant” in Spanish, who just landed on foreign soil and looks lost. The terrain on this northern part of Tierra del Fuego is very flat everywhere, and is very different from anything we have seen on the Punta Arenas side of the Strait of Magellan — you also see hundreds of sheep grazing on the land and a lot of oil development.

When we arrived on land once again, on this huge island known as Tierra del Fuego, meaning “Land of Fire” (so named because of the many bonfires the Native Americans always had burning during the age of Spanish and Portuguese exploration when Ferdinand Magellan first sailed through the strait that now bears his name), we disembarked and I took the following photograph of Diane, the ship, and the calm waters of the strait. I call this photograph la inmigrante, “the female immigrant” in Spanish, who just landed on foreign soil and looks lost. The terrain on this northern part of Tierra del Fuego is very flat everywhere, and is very different from anything we have seen on the Punta Arenas side of the Strait of Magellan — you also see hundreds of sheep grazing on the land and a lot of oil development.

Our plan was to hitchhike to Ushuaia, Argentina, on the Beagle Canal in the southernmost part of Tierra del Fuego. We were fortunate to immediately hitch a ride in the back of a pickup truck eastward to the Chilean village of Cerro Sombrero,  close to the Argentine border in northeastern Tierra del Fuego. The driver was not talkative at all, and he had a rifle in his back window, which was concerning to us in this extremely lonely part of the world. However, everything was cool, literally, as we huddled in the back of his truck for several hours, enjoying the strange landscape. Happily, we were heading eastward on the only road, soon to arrive to “Hat Hill” (the translation of Cerro Sombrero) where we were told we would certainly find a ride south to the “end of the earth,” or at least the end of the South American continent. As this photograph shows, it was also the end of a rainbow, which we interpreted as a very positive sign.

close to the Argentine border in northeastern Tierra del Fuego. The driver was not talkative at all, and he had a rifle in his back window, which was concerning to us in this extremely lonely part of the world. However, everything was cool, literally, as we huddled in the back of his truck for several hours, enjoying the strange landscape. Happily, we were heading eastward on the only road, soon to arrive to “Hat Hill” (the translation of Cerro Sombrero) where we were told we would certainly find a ride south to the “end of the earth,” or at least the end of the South American continent. As this photograph shows, it was also the end of a rainbow, which we interpreted as a very positive sign.

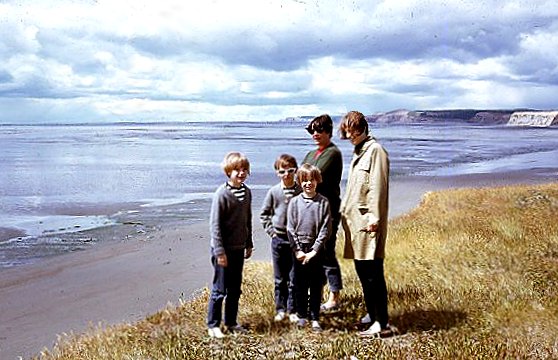

Our missionary friends in Punta Arenas explained that Porteños (people from Buenos Aires) or other Argentinos from Río Gallegos and/or other Argentine coastal towns, often drive to Ushuaia for the holidays, and that we should be able to hitch a ride south, especially because it is a lengthy holiday (between Christmas and New Years). All cars coming from the north have to go through Cerro Sombrero in Chile, and it is the last outpost before making the difficult drive to Ushuaia.  Once we arrived in Cerro Sombrero, a wonderful family (mom, dad, and 3 pre-teen daughters) from Buenos Aires stopped for us and agreed to take us with them to Ushuaia. Dad was an architect in Buenos Aires, Mom was a mom, and the three little girls were little talkative and curious dolls. The family became like our long-lost relatives — they were interested in our lives and we were interested in there’s. We had so much fun speaking Spanish to them and trying to understand their Argentine accents, especially of the little girls. When we asked them donde está tu mamá (“where’s your mother?”), they would reply, something that sounded like sia (sounds like

Once we arrived in Cerro Sombrero, a wonderful family (mom, dad, and 3 pre-teen daughters) from Buenos Aires stopped for us and agreed to take us with them to Ushuaia. Dad was an architect in Buenos Aires, Mom was a mom, and the three little girls were little talkative and curious dolls. The family became like our long-lost relatives — they were interested in our lives and we were interested in there’s. We had so much fun speaking Spanish to them and trying to understand their Argentine accents, especially of the little girls. When we asked them donde está tu mamá (“where’s your mother?”), they would reply, something that sounded like sia (sounds like Asia) jhegó asia, for ya llegó ella (“she just arrived”). Notice in this photograph that the middle daughter is wearing Diane’s white-rimmed dark glasses.

It was a most interesting trip, especially when the road over the mountain pass as we reached the southernmost Andes became mostly mud (first picture below), situated high above the beautiful Lago Fagnano (second picture below). After several unsuccessful attempts to make it over the pass, all of us passengers got out to push, and we finally made it.

Ushuaia in 1967 was a small town on the Beagle Canal, unspoiled by tourism. Diane wrote, “What a contrast Ushuaia is to Punta Arenas! Here, mountains are all around us, and lakes, estuaries, and forests abound — it’s really beautiful! All the houses we have seen are made from wood, many unpainted and stark, while others are brightly tinted. Many have colorful roofs, like this boathouse built on the shore of the Beagle Canal.”

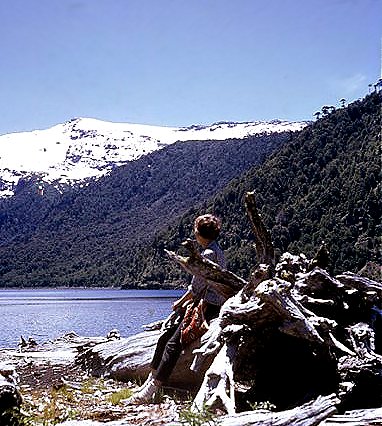

We had no contacts in Ushuaia, but we explained our dilemma and needs to two Canadian clerks (two more of our guardian angels) in an English-speaking Christian book store in the town, and they contacted a local Pentecostal minister who agreed to let us sleep on the floor of his garage, as best we can remember. Either he or his neighbor owned a horse, and Diane, an avid rider, asked if she could have permission to ride the horse around the area. Her wish was granted, and she spent part of our second day in Ushuaia horsback riding on some of the local town dirt roads. I accompanied her on foot and photographed her excursion and the beautiful vistas, as seen in these photographs of the mountain range north of Ushuaia and Ushuaia over 50 years ago.

We had no contacts in Ushuaia, but we explained our dilemma and needs to two Canadian clerks (two more of our guardian angels) in an English-speaking Christian book store in the town, and they contacted a local Pentecostal minister who agreed to let us sleep on the floor of his garage, as best we can remember. Either he or his neighbor owned a horse, and Diane, an avid rider, asked if she could have permission to ride the horse around the area. Her wish was granted, and she spent part of our second day in Ushuaia horsback riding on some of the local town dirt roads. I accompanied her on foot and photographed her excursion and the beautiful vistas, as seen in these photographs of the mountain range north of Ushuaia and Ushuaia over 50 years ago.  Other than the horse, our only transportation around the town was our feet, and Ushuaia is very steep from south to north. We lived up near the top of a hill, and we recall making our hiking easier by saying “push” / “trudge” for our left and right steps. It seemed to help by taking our minds off the physical exertion.

Other than the horse, our only transportation around the town was our feet, and Ushuaia is very steep from south to north. We lived up near the top of a hill, and we recall making our hiking easier by saying “push” / “trudge” for our left and right steps. It seemed to help by taking our minds off the physical exertion.

After a few days of exploring the town, we hitched a ride to the Tierra del Fuego National Park, west of Ushuaia, where we stayed two nights (New Year’s Eve and Day) as guests of the National Park hotel, as Diane explained it in a letter home. “We spent New Years Eve and Day with some Argentine friends (two families) we had made in the National Park of Tierra del Fuego, 20 km west from Ushuaia. We stayed in the National Park hotel for almost nothing because we were “missionaries of peace” as they called us. The only thing we paid for were meals — good thing, too, because we were running out of money. The pay scale is higher in Argentina than in Chile, and everything is very expensive. Thinking in Chilean escudos, the money went fast. In US dollars it wasn’t too bad, because they thought we were “missionaries of peace.” Argentina has never had Peace Corps Volunteers, and the term Cuerpo de Paz was not familiar to the hotel administers. Their understanding of who we were and what we were doing, however, was certainly correct, and we were very thankful for their gift to us.

In the National Park of Tierra del Fuego, west of Ushuaia, we observed wild horses and other wildlife, hiked several trails along the shore of Lago Roca (“Rock Lake”), and enjoyed grilled barbecue steaks with the other guests on New Year’s Eve. We made friends with some of the Argentine guests, and just tried to absorb the beautiful scenery of the snow-capped mountains, lakes, estuaries, and rugged landscapes. Here are four photographs of that memorable place on the southernmost part of Argentina (from the top to bottom are Lago Roca with some new friends; wild horses grazing along the shore of Rock Lake; another view of the lake from the shore; and Diane conversing with other Argentinian National Park visitors at a barbeque on New Year’s Eve, 1967).

Diane wrote, “When we returned to Ushuaia after New Year’s Day we had an interesting experience because we once again stayed with the Pentecostal Minister and wife, but this time we slept in an extra room in the back of their house and we performed music for the Wednesday night service at their church. Dale played hymn melodies on his flute and I sang alto. Their service wasn’t so different from ours [we are lifelong Baptists], really, except that everyone prayed out loud at the same time. They knew the same hymns we did, like The Old Rugged cross, In the Garden, What a Friend we have in Jesus, Ivory Palaces, and others.” Music has such wonderful powers of communication, building friendships, and creating trust, and the opportunity we had to share our God-given gifts with fellow believers at the bottom of the Western Hemisphere in Ushuaia, Argentina, was an awesome experience.

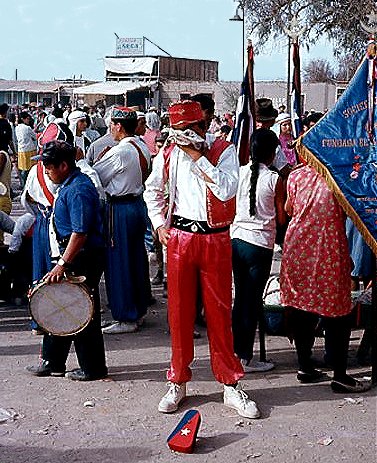

Late evenings in Ushuaia during the summer months of December and January are spectacular because it is light almost all night, being so close to Antarctica.  One of the sights that has always stuck in our minds