This introduction to the music of the Warao is like an EXCURSION through the rainforest musical world of an Amerindian “nation” in peril, as the Warao attempt to culturally survive in 21st century Venezuela and the world. The excursion begins by focusing on several aspects of Warao secular music and musical instruments, such as the lullaby, the deer bone flute, the violin, and the drum. By using song texts and folk tales (which are like Warao history books), aspects of the Warao world view and beliefs are introduced. It continues by looking at music and shamanism among the Warao of Venezuela (look at this link of Latin American rain forest maps, and click on various countries to see the breadth of the forested areas in South America).

This introduction to the music of the Warao is like an EXCURSION through the rainforest musical world of an Amerindian “nation” in peril, as the Warao attempt to culturally survive in 21st century Venezuela and the world. The excursion begins by focusing on several aspects of Warao secular music and musical instruments, such as the lullaby, the deer bone flute, the violin, and the drum. By using song texts and folk tales (which are like Warao history books), aspects of the Warao world view and beliefs are introduced. It continues by looking at music and shamanism among the Warao of Venezuela (look at this link of Latin American rain forest maps, and click on various countries to see the breadth of the forested areas in South America).

One of the most important contexts for music within the South American rain forest cultures is shamanism. A shaman is an individual who communicates with the supernatural for purposes of maintaining order in both the mortal and immortal worlds. He (or less often, she) usually does this by singing, because song is a special form of communication between humans and their spiritual advisors, protectors, and adversaries. The most powerful tool of the Warao wisiratu shaman is a huge rattle called hebu mataro. (In the picture to the right, a Warao shaman is seen returning from the house of a seriously ill man; later that evening he sang over the man for hours, using his hebu mataro rattle, in an attempt to cure him.)

THE EXCURSION BEGINS

(1) The rain forest setting of the Warao: the Delta of the Orinoco River, Venezuela

The Warao are a native American people who live in the lower Orinoco River rain forest of Venezuela (when you scroll down to the map in this link, the Orinoco River Delta area is referred to as an “inland swamp“). Their name for themselves (their autodesignation) translates as ‘Canoe People’ (wa = canoe, arao = owners of).

The Warao are a native American people who live in the lower Orinoco River rain forest of Venezuela (when you scroll down to the map in this link, the Orinoco River Delta area is referred to as an “inland swamp“). Their name for themselves (their autodesignation) translates as ‘Canoe People’ (wa = canoe, arao = owners of).

The Orinoco River Delta, known as the Delta Amacuro Federal Territory, is an intricate web or maze of rivers and streams that covers approximately 10,200 square miles of one of the few remaining tropical rain forests of northern South America. The area is easily navigable by canoe and other shoal draft boats. There are no rapids, no cataracts, and few obstacles except for shoals during low tide or the dry season, felled trees blocking one’s path, or flotsam. There are no dangerous animals, few snakes, and, except for the possibility of sting rays, electric eels, piranhas, and other water life with which one should not come into contact, few threats exist above or beneath the water.

The majority of the Warao (also spelled Warrau, Guarao) group themselves together in extended families and live in piling houses along the swampy shores of rivers (see the picture to the right). Because of the nature of the Orinoco River Delta, the Warao are a riverine fishing people. Today they have also added horticulture to their food quest activities.

The majority of the Warao (also spelled Warrau, Guarao) group themselves together in extended families and live in piling houses along the swampy shores of rivers (see the picture to the right). Because of the nature of the Orinoco River Delta, the Warao are a riverine fishing people. Today they have also added horticulture to their food quest activities.

Extensive missionization did not begin until 1925 when Spanish Capuchin missionaries began to establish mission schools in the Delta. Other acculturative forces of recent times in the area include Creole built and owned sawmills with their attraction of buyers, sellers, traders, adventurers, and frontiersmen from the outside; oil exploration teams; road and dike builders; Creole settlers; and anthropologists and other scientists.

Today the Warao number approximately 19,500 individuals grouped into about 250 villages throughout the central Orinoco Delta. The most isolated and also the most “traditional” Warao are those who live in the central delta of the Orinoco, on the Winikina River. In the area the villagers live, fish, hunt, gather food, play, move about in their canoes.

Today the Warao number approximately 19,500 individuals grouped into about 250 villages throughout the central Orinoco Delta. The most isolated and also the most “traditional” Warao are those who live in the central delta of the Orinoco, on the Winikina River. In the area the villagers live, fish, hunt, gather food, play, move about in their canoes.

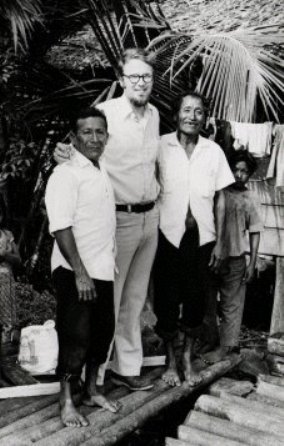

For a number of months in 1972, 1973, and again in 1974, I lived in the village of Yaruara Akoho on the Winikina River (situated within the circle on the above map of the Orinoco Delta), conducting research on the music of the Warao. I lived in the village school house (which was built on cement pilings), slept in a hammock, ate mostly rice and canned sardines, drank rain water collected from my roof, and bathed only when it rained (nearly every day). The above picture shows me with two of my most important friends and teachers (now both deceased). My research with the Warao resulted in a dissertation about music and shamanism of the Warao (Ph.D. 1973, UCLA), several articles in journals, and a book (see picture of front cover below) titled Music of the Warao: Song People of the Rain Forest (University Press of Florida, 1996).

Let’s continue to look at how music exists within the daily life of the Warao, because Warao people enjoy music, and they especially like to sing. Both men and women sing while they work and care for their children; children sing while they play; and many Warao of all ages often sing while relaxing in their hammocks. Shamans sing while they cure illnesses and contact Warao spirits; other religious leaders or elders sing ceremonial songs during rituals; and anyone can sing certain magical songs for protection or healing. Some Warao men play musical instruments, but not the women.

(2) The cultural significance and use of the Warao lullaby, and the meaning of the term “enculturation”

The primary utilitarian song type among the Warao is the lullaby, which actually has two functions. First, the lullaby soothes the child, not so much with its delivery which is harsh and loud by European derived standards, but by the presence of a familiar person (mother, father, brother, sister, grandparent, etc.) with her or his familiar voice.

Its more important function, however, is to be a vehicle for informal education—the texts of Warao lullabies are improvised to predetermined melodic patterns, and they address certain areas of Warao mythology and daily life. In other words, they teach the adolescent children (not the infant, who is too young to understand song texts) about Warao beliefs and existence.

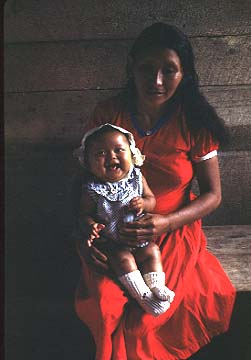

Warao lullabies are usually sung by an adult member of the family, often a parent or grandparent. The song texts begin with gentle commands addressed to the baby, telling it to go to sleep and not to cry. Following these introductory supplications are several textual themes, such as reference to the absence of a parent who is away working in the rain forest, cutting trees or searching for food. The following lullaby, sung by the grandfather of the infant girl in this picture (she is held by her mother), tells about parental roles regarding food quest and infant feeding requirements.

1-1 – Lullaby sung by a mother

Don’t cry, go to sleep my little child.

Your mother went to look for food; she is looking for grub worms.

When she returns we are going to eat.

Your mother has not returned yet from there.

When she returns we will not give you anything,

because you don’t know how to eat yet.

Your father went without us.

Don’t cry, go to sleep.

This lullaby explains how the infant’s mother and father are in the rain forest gathering food (in this case grub worms), and how the baby cannot yet eat solid food.

Many of the Warao lullabies describe animals and spirits of the rain forest, most of them potentially dangerous. The majority of the animal lullabies are about jaguars: some refer to the physical characteristics of the jaguar, while others are about the jaguar’s desire to eat babies. The song texts often tell the infant to go to sleep or it will be eaten by a supernatural jaguar (or some other infant-eating animal or spirit). The following lullaby was sung by my neighbor for his infant son; it’s about a boneless jaguar:

1-2 – Lullaby sung by a grandfather

Nearby in the rain forest the jaguar is listening to us.

The head of the jaguar has no bones, it is pure flesh.

The jaguar is near, and it has a good head [it is smart] and can learn and speak Warao.

It is learning my words and my family’s words.

My son, I am your father.

The jaguar thinks hard, learning my words.

It is listening to us, so go to sleep.

Your mother went to look for food this afternoon.

If she brings food we’ll eat.

If not, we’ll go to sleep without eating.

In addition to warning about the boneless and flesh-eating jaguar, this lullaby also mentions the working mother. In a way it is preparing the adolescent children for physical and supernatural dangers, and also about the possibility of going hungry.

To a non Warao, the texts of the Warao lullabies may appear to be overly frightening for children. The idea of “go to sleep or else,” however, is not unfamiliar to North Americans and Europeans as we think of our own familiar cradle song with the following text: “Rockabye baby, in the tree top. When the wind blows the cradle will rock. When the wind blows the cradle will fall, and down will come baby, cradle and all.” Many Native American lullabies appear to be frightening, while at the same time they are generally positive because they informally educate the older children who are nearby in their hammocks listening, subconsciously being prepared by their elders for the supernatural part of their world and its dangers, as well as being indirectly educated about parental chores, eating times, the types of food an infant cannot eat, and so forth. This technique of informal learning is also called “enculturation.” While certain types of informal learning take place during infancy, learning through listening to songs takes place during childhood and adolescence as the children themselves learn to speak and comprehend the Warao language.

(3) Three types of musical instruments of the Warao: muhusemoi (flute), sekeseke (violin), and ehuru (drum)

At one time the Warao possessed at least fifteen musical and other sound instruments that were used in shamanistic rituals, non shamanistic ceremonies, signaling, and entertainment. Of this number today, several are either rare, no longer used, or extinct (their memory lives on in Warao narratives, however). The ten surviving musical instruments are two types of container rattles, one strung rattle, two “flutes,” one “clarinet,” two “trumpets,” one double-headed skin drum, and one bowed “violin.” In this section we will study only the most common Warao instruments: the muhusemoi flute, the sekeseke violin, and the ehuru drum.

muhusemoi

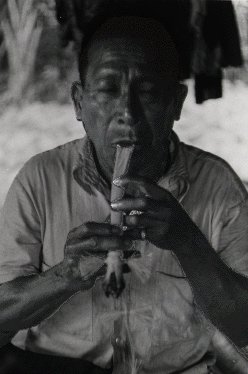

One of the most frequently seen and heard aerophones among the Warao is the muhusemoi (muhu = bone, semoi = wind instrument), a ductless vertical flute made from the tibia of a deer. Several of my Warao friends made deer bone flutes for me, and my best friend and teacher, Antonio Lorenzano (seen in this picture), taught me how to play it by giving me weekly instruction. Through music lessons I learned that the Warao flutist has a unique way of fingering his instrument, unlike any other method of fingering with which I was familiar. The Warao method is to open the bottom finger hole, close it, open the middle finger hole, close it, and open the upper finger hole and close it. In other words, only one hole is open at a time, creating a scale unlike any others.

One of the most frequently seen and heard aerophones among the Warao is the muhusemoi (muhu = bone, semoi = wind instrument), a ductless vertical flute made from the tibia of a deer. Several of my Warao friends made deer bone flutes for me, and my best friend and teacher, Antonio Lorenzano (seen in this picture), taught me how to play it by giving me weekly instruction. Through music lessons I learned that the Warao flutist has a unique way of fingering his instrument, unlike any other method of fingering with which I was familiar. The Warao method is to open the bottom finger hole, close it, open the middle finger hole, close it, and open the upper finger hole and close it. In other words, only one hole is open at a time, creating a scale unlike any others.

How does the flute maker construct his instrument? First he has to kill a deer (usually the chief of each village owns a shotgun). After he has acquired a suitable deer tibia, he opens both ends of the bone and removes as much marrow as he can with a knife. Then he places the bone in a place out of the reach of dogs, but within the reach of cockroaches which eat out the marrow within several days. After about a month he carves a saddle shaped (a wide notch) mouthpiece into the proximal end of the bone with a knife. Then he places the mouthpiece edge within the crotch between his thumb and first finger (using his fingers as rulers for finger hole placement). Where the tip of his first finger falls he will drill the bottom finger hole with the sharpened point of a harpoon in the fashion of a fire drill, a technique requiring only about one minute effort per finger hole, depending on the sharpness of the harpoon point. The maker then measures the distance for the second finger hole with the back of his thumb (from the tip of the thumb to the first joint) and drills it with similar ease. The same techniques are used to determine the placement of the third finger hole and drill it out. Since Warao hands and Orinoco Delta deer tibias all differ in size, there is naturally a difference in the resulting pitches of the final products. Then the maker tests his finished flute.

1-3 – Two men playing muhusemoi deer bone flutes

In this example notice how the two instruments are pitched a fourth apart, and how the musicians play the same melody in a type of canon (i.e., close imitation) like a round, each giving free reign to individual expression while maintaining a similar pulse.

Muhusemoi flutes are played in several contexts. They can be played with the Warao drum for contentment (and perhaps to scare away the animals?) while going into the rain forest to cut down a certain tree for making facial paint. Another Warao musician explained to me that two flutes are played in the rain forest by several men while other family members fell particular palm trees for making sacred cakes. Another context is the harvest dance festival, when several muhusemoi flutes are played with other instruments (such as the sacred Warao “clarinet”), making up a type of orchestra used for the sacred dance during the nahanamu harvest festival.

1-4 – Nahanamu harvest festival music

sekeseke

Some Warao men play a handmade violin, called sekeseke, which they consider to be one of their traditional instruments. While it is often a crude representation of a European violin, sometimes the sekeseke is virtually the same as the classical Western instrument. The instrument used by my friend Menegildo in Yaruaro Akoho (seen in the above picture) is a close copy of a typical European violin. The bow, however, which is drawn across the sekeseke’s strings, resembles a European bow from the Spanish Renaissance period, rather than a modern violin bow (it has a convex rather than a concave curve). Moreover, the way Menegildo holds his bow is not consistent with modern violin playing.

Some Warao men play a handmade violin, called sekeseke, which they consider to be one of their traditional instruments. While it is often a crude representation of a European violin, sometimes the sekeseke is virtually the same as the classical Western instrument. The instrument used by my friend Menegildo in Yaruaro Akoho (seen in the above picture) is a close copy of a typical European violin. The bow, however, which is drawn across the sekeseke’s strings, resembles a European bow from the Spanish Renaissance period, rather than a modern violin bow (it has a convex rather than a concave curve). Moreover, the way Menegildo holds his bow is not consistent with modern violin playing.

According to Warao folklore the sekeseke was invented, first built, and sent to the Warao in a ship by a monkey from a far-off land. This mythical creature, who had the upper torso of a man and the lower torso of a monkey, learned how to make the violin in a dream. The late Antonio Lorenzano, my Warao friend and teacher, related the following narrative to me in 1972 about the origin and magical protective power of the sekeseke:

This is the story about the origin of the sekeseke which was made by a monkey. The monkey dreamed one night, and in the dream he made a sekeseke. During the dream the monkey cut a piece of wood from afar, not here but found over there. It was a piece of cedar, similar to the cedar found around here. He cut it with a machete, and with his knife he made the little head and the place where the strings go. Thus the monkey dreamed, and when he woke up he knew how to make the sekeseke. He said “Wow, what a great dream I had. Today I’m going to make a sekeseke like I made in my dream last night. I’m also going to make a boat, a very large one, because people from other countries have never seen this.” Then the monkey got up and began to make the sekeseke. First he cut a piece of cedar, similar to the wood from afar. The wood that he used in the dream is not the same as the wood of the earth. Now, during the day he cut wood that is from this world; he cut cedar. He carved it well, and with his knife he refined it and made the little holes on each side. He made the little head and made a little hole behind it. Then in the middle, where he made the double holes on each part, he attached the bridge. Over this he placed the strings; the first, second, third, and fourth; four strings. Violin, four, sekeseke. Now, as he did in the dream, he made a bow. Then the monkey tried it out. It sounded good when the bow was drawn across the strings. All the songs sounded good. Therefore, it was ready.

The jaguar didn’t know anything about this. He is dumb, lazy, and is good for nothing. He doesn’t know anything and is a brute. The jaguar thought, “Hey, tomorrow I am going to kill and eat the monkey.” Then he slept, and when it was about dawn he sent a message to the monkey: “Look, friend monkey, be prepared. You know that today I am going to kill you and eat you.” The monkey said, “Who’s going to attack me today?” “The jaguar,” was the answer. “Aha,” said the monkey, “now that I have my violin already made, it’s okay, let him come. If he kills me and eats me, it doesn’t matter. It’s not important to me. But before he kills me and eats me I am going to play some beautiful music for him. After that he can kill me and eat me.” The jaguar said, “Now is the time. At eight or nine o’clock I will arrive there, precisely to kill this monkey and eat him, nothing more.” So, at eight or nine o’clock the jaguar came. But before he arrived, the music was all prepared by the monkey. When the jaguar got there he said, “Well monkey, today is the last day of your life. Pretty soon I am going to kill you and eat you.” The monkey answered him, “Just one little minute jaguar; before you kill and eat me I’m going to play some music for you. Afterwards you can kill me and eat me.” Thus, the monkey passed his bow over his violin and the music was the best ever heard. The jaguar, the deer, the agure, the howler monkey, and all kinds of birds gathered around the monkey. When the bow passed over the strings of the violin all the animals stood up and began to dance. The jaguar danced, the birds danced, everybody danced, and the music they heard was the most beautiful ever. They danced until they were tired of dancing. “It’s good, stop, we’re tired. Ah, such beautiful music!” said the jaguar. “Good, my monkey friend, it’s alright. I thought you were a brute and that you didn’t know anything about music.” Yes, my friend jaguar,” replied the monkey, “I am your friend, your cousin. I have been a musician from the time I was very little. I am the one who made this sekeseke, the strings, the bow, the song, everything. Now you must not eat me.” “Certainly not,” said the jaguar, “because you are a musician.” This is the end of the story, my friend.

While the theme of this narrative is the power of music (to sooth the savage beast?), the sole use of the sekeseke among the present Warao is for entertainment. It is most often performed by an individual male for his own satisfaction, with family members nearby tending to their chores. Its repertoire primarily includes dance songs for listening pleasure rather than for dance (the original dance function is extinct).

ehuru

This is the only drum or membranophone of the Warao. It has two skins made from howler monkey hide, and one of the skins has a snare that consists of a string and a thorn. This causes the sound to vibrate, as you can hear in the music. The drum is played with one drumstick, and the body of the drum has a slight hourglass shape. The ehuru is used most often for leading a group of people walking through the rain forest. With its sound the leader of the single-file can let those behind him know where he, the leader, is. It is easy to get lost while walking in the rain forest of the Orinoco Delta. The ehuru can also accompany songs, such as you can hear in the following example.

1-5 – Male song accompanied by ehuru drum

NOT INCLUDED (available on CD that accompanies book)

The song text makes no reference to walking in the rain forest; this is perhaps because the song was recorded out of context in the school house, and also because the singer sang a shortened version of the song for me to record.

(4) Warao cosmology and religion

The Warao concept of their universe is complex, and certain aspects of Warao cosmology are perhaps influenced by natural geographic and astronomical phenomena visible in the Orinoco Delta region of Venezuela and adjacent areas. For example, the Warao view their world as surrounded by water, which it nearly is. In the middle of their cosmic sea is the land mass upon which they live, flat and shaped like a disk. Beneath their earth lies a lower world inhabited by a double-headed snake that encircles the earth, exposed, at times, like a sandy beach, with its two heads spaced apart to create an opening towards the east, just as the mouth of the Orinoco River creates an opening into the Atlantic Ocean. The snake’s movements are believed to cause the ebb and flow of the tides. The Warao live at the center of this land mass, while at each of the cardinal and inter cardinal points, across the water and at the very ends of the world, are sacred mountains or pillars upon which certain deities dwell. Each of these supreme beings is known as kanobo, which literally means “our ancient one” or “our grandfather.”

The kanobo of the southern mountain resembles a toad, although it can also assume a human form. The kanobo on the sacred mountain in the north (which is an actual hill, named Nabarimi Hill, on the western coast of southern Trinidad) is known as the “Father of the Waves.” The kanobo of the eastern cosmic mountain is the unapproachable god of origin. The geographic equivalent of his abode does not exist because it is in the Atlantic Ocean. His son, called the “Creator Bird of the Dawn,” is represented by a swallow-tailed kite. Because it is situated at the end of the universe where the sun rises, this easternmost cosmic zone (called hokonemu in shamanistic texts) is most sacred to the Warao. It is the realm of light, is misty like dawn and tobacco smoke, and is the cosmological sector associated with bahanarotu shamanism. In the eschatology of the Warao it is a highly sought after place to spend eternity. The western extreme of the Warao universe, by contrast, is the world mountain of the god of the underworld and the supreme Hoa spirit, called Hoebo—he is embodied by a deified scarlet macaw. This cosmic world is the ominous end of the universe where the sun sets, symbolized by the fiery sky of dusk (seen in the picture to the right), the bright feathers of the scarlet macaw, and the redness of human blood. It is the eternal place of death and darkness, the region of the cosmos associated with hoarotu shamanism. In the eschatology of the Warao, this is a terrible place to end up.

The kanobo of the southern mountain resembles a toad, although it can also assume a human form. The kanobo on the sacred mountain in the north (which is an actual hill, named Nabarimi Hill, on the western coast of southern Trinidad) is known as the “Father of the Waves.” The kanobo of the eastern cosmic mountain is the unapproachable god of origin. The geographic equivalent of his abode does not exist because it is in the Atlantic Ocean. His son, called the “Creator Bird of the Dawn,” is represented by a swallow-tailed kite. Because it is situated at the end of the universe where the sun rises, this easternmost cosmic zone (called hokonemu in shamanistic texts) is most sacred to the Warao. It is the realm of light, is misty like dawn and tobacco smoke, and is the cosmological sector associated with bahanarotu shamanism. In the eschatology of the Warao it is a highly sought after place to spend eternity. The western extreme of the Warao universe, by contrast, is the world mountain of the god of the underworld and the supreme Hoa spirit, called Hoebo—he is embodied by a deified scarlet macaw. This cosmic world is the ominous end of the universe where the sun sets, symbolized by the fiery sky of dusk (seen in the picture to the right), the bright feathers of the scarlet macaw, and the redness of human blood. It is the eternal place of death and darkness, the region of the cosmos associated with hoarotu shamanism. In the eschatology of the Warao, this is a terrible place to end up.

Covering this complex Warao universe of water, land, sacred mountains, serpents, light and darkness, is a celestial dome, shaped somewhat like an Indonesian knobbed gong or a Frisbee. Connected from its apex to the center of the earth by an axis mundi, or central pathway embedded from beneath the earth like a celestial tree, Warao shamans ascend the dome and travel to the world mountains via celestial roads. The apex of the dome is inhabited by additional, though lesser ranked, deities known as hebutuma (plural of hebu)–-–ancestor spirits. The most important hebu is the first wisiratu shaman, who ascended the axis mundi (the center of the cosmic world) with his sacred hebu mataro rattle.

Warao shamans or religious practitioners (wisiratu, bahanarotu, and hoarotu) frequently travel the celestial paths of the Warao universe. Without their supernatural knowledge, the Warao would have no life after death, and their lives on earth would be meaningless. Additionally, the hebu ancestor spirits can cause sickness and death to the Warao, and they frequently visit earth to do so. Shamans are the only mediators between the mortal and immortal, and with their powers and knowledge they can cure illness and maintain stability in the Warao world.

The most frequent shamanistic context for song among the Warao is the curing of illnesse, which points to one very important function of Warao music: to furnish the singer with power. This power is essential to the Warao because of their preoccupation with death and dying. Most, if not all, Warao deaths are believed to be caused by the actions of supernatural powers; however, there are three levels of supernatural causes—hebu, bahana, and Hoa.

According to the eschatological beliefs of the Warao, almost all dead souls are destined to go to a particular place, depending upon the dead person’s occupation during life. Two exceptions to this are adults believed to have been killed by Hoa (spirit powers in the western cosmic realm), and children who, until adolescence, are believed not to have souls. The largest number of deaths among the Warao is among the children—the infant mortality rate, at 49 percent, is especially high.

The death of a Warao child is not taken lightly by the members of the child’s village—all the villagers are related to the deceased by either blood or marriage. When I arrived at the village of Yaruara Akoho in the summer of 1974 a child had just died. The entire village was in mourning, many of the men were (ritually) drunk, and the women were wailing (see also Charles Briggs 1993). After several days of quiet observation on my part, and when the village seemed to have returned to normal, I noticed a number of women leaving by canoe. My male friends explained to me that the women were going to check the canoe in which the deceased child was buried, to see if there were any bird tracks in the mud within which the body had been encased. I also learned that a corpse, waba in Warao (meaning “dead”) is buried in a wa or canoe; it is wrapped in a hammock, placed in a dugout canoe, and packed in mud. The canoe-coffin is placed above the ground on poles in a Warao cemetery, not too far from the village. According to Warao belief, a certain bird will visit the burial place and leave its tracks in the mud if the deceased was killed by Hoa.

Concern over life and death, then, is of utmost concern for the Warao. In spite of the seventy-five years (since ca. 1925) of contact with Roman Catholicism through the Spanish Capuchín order, Warao traditional eschatological beliefs prevail. Christianity has functioned mainly as a parallel pathway for assuring a happy life after death, rather than as a replacement of the more ancient and traditional Warao ideology.

(5) The cultural significance and symbolism of the sacred hebu mataro rattle

The hebu mataro, a sacred instrument used almost exclusively by the wisiratu shaman, is a spiked vessel or container rattle idiophone made from a large fruit of the calabash tree (the fruit, known to us as a calabash, is often confused with a gourd—the former grows on a tree and the latter grows on the ground). The maker of the rattle cuts four slits into the large calabash, two vertical and two horizontal slits into the sides. The spike that pierces the calabash, forming both the uppermost projection and the handle of the rattle, is made from a stick of wood that is the same type of wood used by the Warao for their fire-making drills. The empty calabash is then filled with many (50 to 200) small pea-sized quartz pebbles.

The hebu mataro, a sacred instrument used almost exclusively by the wisiratu shaman, is a spiked vessel or container rattle idiophone made from a large fruit of the calabash tree (the fruit, known to us as a calabash, is often confused with a gourd—the former grows on a tree and the latter grows on the ground). The maker of the rattle cuts four slits into the large calabash, two vertical and two horizontal slits into the sides. The spike that pierces the calabash, forming both the uppermost projection and the handle of the rattle, is made from a stick of wood that is the same type of wood used by the Warao for their fire-making drills. The empty calabash is then filled with many (50 to 200) small pea-sized quartz pebbles.

The rattle is often adorned with bird feathers at the apex of the wooden spike that protrudes from the calabash. Selected red and yellow tail feathers taken from a live parrot are sewn into a long sash (as seen in this picture) that is wound around the tip of the stick.The construction of a hebu mataro rattle is not easy, because it is difficult for the maker (the wisiratu shaman) to obtain all of the required materials.

The hebu mataro rattle is one of the most powerful musical instruments in the practice of Warao religion, both for curing certain types illnesses and in individual and group religious practices of the wisiratu shaman. Are there meanings attached to of all these parts of the shaman’s hebu mataro rattle? Yes, there are powerful meanings, as with any religious icon. The shaman’s rattle is considered to be a “head spirit”: the calabash is the head, the wooden handle is the neck (some say the leg), the feathers are the hair, the slits are the mouth(s), the geometric decorations around the slits are the teeth, and the sound produced by the pebbles rattling inside is the voice of the spirit. Together these metaphors combine to make a powerful helping spirit for the wisiratu shaman. Furthermore, when the rattle is vigorously shaken during a curing ceremony, the quartz pebbles produce heat, causing the dust of the calabash and the stick (with its low flash point, as in the wood’s use as a fire drill) to ignite and produce glowing embers. Listen now to the following musical example.

The hebu mataro rattle is one of the most powerful musical instruments in the practice of Warao religion, both for curing certain types illnesses and in individual and group religious practices of the wisiratu shaman. Are there meanings attached to of all these parts of the shaman’s hebu mataro rattle? Yes, there are powerful meanings, as with any religious icon. The shaman’s rattle is considered to be a “head spirit”: the calabash is the head, the wooden handle is the neck (some say the leg), the feathers are the hair, the slits are the mouth(s), the geometric decorations around the slits are the teeth, and the sound produced by the pebbles rattling inside is the voice of the spirit. Together these metaphors combine to make a powerful helping spirit for the wisiratu shaman. Furthermore, when the rattle is vigorously shaken during a curing ceremony, the quartz pebbles produce heat, causing the dust of the calabash and the stick (with its low flash point, as in the wood’s use as a fire drill) to ignite and produce glowing embers. Listen now to the following musical example.

1-6 – Wisiratu shamanistic curing song with hebu mataru rattle

(6) Warao shamanism and three types of Warao shamans: wisiratu, bahanarotu, and hoarotu

According to the Warao world view there are three types of cosmological practitioners that can be classified as shamans–-–wisiratu, bahanarotu, and hoarotu. One of the most important duties of any shaman is curing illnesses. Through a technique of ecstasy that is culturally induced with the aid of music and tobacco smoke (less of the latter than the former), a shaman is believed to be transformed into a powerful being which is able to sustain contact with the spirit world for the purpose of re-establishing order and balance in Warao society. There are three types of shaman because of the three major cosmic realms discussed above: the central, eastern, and western. Each of these three realms are the cosmological areas from whence come three different types of illness that can lead to death. To cure such illnesses requires the aid of the appropriate shamanic specialist. Only the shaman himself, with the assistance of his spirit helpers that reside within his body, can figure out what harmful essence (with power from one of the cosmological realms) caused the illness. It is up to him to effect a cure. To do so, the shaman must “name” the illness-causing essence through his curing song. When properly named, through a type of “cosmic diplomacy” with the spirits, the shaman removes the essence by massage or suction (see further Olsen 2008).

Wisiratu

The wisiratu cures hebu (ancestor spirit) sicknesses that are caused by the intrusion of a metaphysical essence into a victim’s body, thereby causing pain, fever, and even death. The wisiratu, with powerful assistance from his hebu mataro sacred rattle, attempts to name the essence and remove it with massage. As you listen to the example, you will hear the loud shaking of the rattle by the shaman as he sings.

1-7 – Wisiratu shamanistic curing ritual

The typical curing song cycle of the wisiratu shaman includes three sections (A, B, and C). The first (which I call A) is for calling his helping spirits that he has within his chest. When he calls these helpers through song, the wisiratu masks his voice and sings with a very growly tone quality. Voice masking is often used for supernatural communication. In the second section (which I call B), the wisiratu attempts to “name” the illness-causing spiritual essence that is within the patient, causing sickness. In this section voice masking is not used, because the shaman is transformed into a spirit himself. The melody of this section is more extensive than the first section, and is longer. During this B section the wisiratu can name a variety of hebu spirits. The shaman’s C section is a one note recitation-dialogue, in which the wisiratu is usually answered by his assistant or sings an answer by using ventriliquism. This short section is when the illness-causing hebu speaks with the shaman. A typical curing sequence includes a number of these musical sections, in a variety of orders, but most often A, B, C, B, C, B.

The typical curing song cycle of the wisiratu shaman includes three sections (A, B, and C). The first (which I call A) is for calling his helping spirits that he has within his chest. When he calls these helpers through song, the wisiratu masks his voice and sings with a very growly tone quality. Voice masking is often used for supernatural communication. In the second section (which I call B), the wisiratu attempts to “name” the illness-causing spiritual essence that is within the patient, causing sickness. In this section voice masking is not used, because the shaman is transformed into a spirit himself. The melody of this section is more extensive than the first section, and is longer. During this B section the wisiratu can name a variety of hebu spirits. The shaman’s C section is a one note recitation-dialogue, in which the wisiratu is usually answered by his assistant or sings an answer by using ventriliquism. This short section is when the illness-causing hebu speaks with the shaman. A typical curing sequence includes a number of these musical sections, in a variety of orders, but most often A, B, C, B, C, B.

Bahanarotu

The bahanarotu cures physical ailments caused by bahana, which is the spiritual essence of some material object that has been placed into the body of a victim by a malicious bahanarotu or bahanarotu soul, with special powers acquired from the eastern cosmic realm. The bahanarotu shaman uses suction to remove the spiritual essence of an object from his patient’s body. One evening in 1972 I witnessed a bahanarotu remove a piece of nylon rope (from the patient’s head) and a rusty nail (from the patient’s neck) from a female victim. After removing the spiritual essences, the shaman produced the two saliva-covered objects and passed them around for us to view with our flashlights. These, he explained, were causing the patient’s illness.

Hoarotu

The hoarotu cures patients who suffer from Hoa, a spiritual essence that can emanate from any tangible or intangible thing. This type of illness, which derives its power from the western cosmic realm, is the worst kind among the Warao. There are few people who can survive a Hoa illness.

When the Warao hoarotu shaman sings to cure illness, his most important power element is the “naming” of the illness-causing spirit essence. Therefore, the curing hoarotu must name the spirit essence that is within the patient, causing him or her the illness. Because there are innumerable spirit essences that could have been named and placed into the patient and the inflicting hoarotu, the curing hoarotu often cannot name the correct essence. For this reason, sometimes multiple hoarotu shamans are called upon to cure, singing together in duet or trio (or even larger numbers) to try to effect a cure. One of the curing sessions I experienced was performed by three men, each singing the hoarotu curing melody at different pitches and with different words. Their objective was to cure a very important member of their village who had been struck down by an unknown cause (a stroke according to the Catholic missionery in the area, and a Hoa intrusion according to the shamans). Listen to a portion of that curing ritual which I recorded deep in the Warao rain forest in 1972.

1-9 – Hoarotu curing ritual performed by three shamans

The man did survive, and the curing hoarotu shamans received the credit; he was one of the lucky ones to have survived Hoa illness, according to them.

CULTURAL SURVIVAL

The traditional use of music among the Warao Indians of the Orinoco River deltaic rain forest is to provide the Warao with supernatural power to inflict illness and death, cure and heal, protect, cause rain, and educate. Yet, the Warao suffer from and have no control over the powers of governments and businesses, as oil and drug cartels invade and threaten to destroy their part of the fragile rainforest, urban homelessness and prostitution develop, and eco-tourism treats the area and it inhabitants as a theme park. While the information and musical examples in this “Ethnomusicology as Advocacy” case study inform about the Warao, how can that information help find solutions leading towards Warao cultural survival? The first step is to develop an appreciation for Warao musical and cultural expressions and to try to understand their significance for the Warao and humankind in general. If we can learn to appreciate and understand Warao music, then perhaps we can learn to appreciate the Warao as a culture and love them as people.

Envasion by big business (oil exploration, drug cartels, and more)

Cultural exploitation is a terrible thing, something that governments and businesses are not often concerned about. What often happens after cultural exploitation is usually sad and unforgiving. While living in the Orinoco Delta I saw some minor events taking place that I felt caused the Warao some cultural and personal anguish (deforestation; financial exploitation at “company stores”; changing food patterns because of introduction of white rice and sugar; and other rather insignificant changes). It wasn’t until I read a National Geographic article on the Orinoco River, however, that I discovered that recent events include drug cartels using the hundreds of secluded deltaic waterways for transporting narcotics out of South America, and oil companies are exploring the region for possible oil drilling; some have already erected oil rigs. A number of Internet links (NO LONGER AVAILABLE) are included below that elaborate on recent problems and possible solutions to the cultural exploitation of the Warao in Venezuela by big businesses.

- “Environmentalists and Warao Indian Tribe Headed for Conflict with Oil Explorers“(Caracas: February 15, 1997)

- “VENEZUELA-INDIGENOUS: Waraos Analyse Impact of Oil Drilling” (Caracas: March 20, 1997)

- “The Downside of Oil Concessions” (Caracas: April 8, 1997)

- “VENEZUELA: Survival International Demands Government Suspenion Of Oil Concessions Along The Rio Orinoco” (Caracas: April 17, 1997)

Urban Homelessness and Prostitution

As economic conditions for the Warao worsen, because of the deforestation of their fragile Orinoco Delta that leads to the extermination of natural animal and plant foods, a number of Warao have migrated to urban areas, especially Caracas, a large and dangerous city for the indigenous newcomers that are unfamiliar with modern urban living. Like other migrants to the cities, the Warao seek a better life. Like many others, they end up as slum dwellers or worse: as homeless and disoriented street people. The situation is especially sorrowful for Warao women and children, whose only solution, they think, is prostitution and crime. The following Internet article (NO LONGER AVAILABLE) creates an awareness of some of the plights of the Warao homeless in urban areas of Venezuela:

- “Poverty, Disease, Oil Exploration and Logging Drive Warao Indians to Venezuela’s Cities” by Alexandra Olson (Associated Press, October 7, 2001)

Eco-tourism

I have not yet concluded if eco-tourism threatens the Warao and the Orinoco Delta in general. Unlike in Costa Rica, where the eco-tourism of native peoples is in the hands of the native people themselves, the Warao have no such power over their tourism destiny. Most of the articles published on the Internet are promotional, and many contain misinformation about Warao culture, oversimplifying the people and exoticizing the people and their traditions. Nevertheless, they feature beautiful photography and friendly discourse (like I said, they are promotional). The following Internet articles (NO LONGER AVAILABLE) provide examples relating to eco-tours in the Orinoco Delta:

- “No blues in this delta” by Stephanie Fox (telegraph.co.uk, May 4, 2004)

- “Orinoco Delta” (Angel-Eco Tours)

- “Tour Orinoco-Delta” (www.fulldayturismo.com)

- “Orinoco Delta School” (Orinoco Delta Lodge, Tucupita Expeditions, www.orinocodelta.com)

Solutions

What can be done to help the Warao Indians of Venezuela, and others like them? The first step is awareness. You could surf the web yourself by entering the word “Warao” into www.google.com (in October, 2004, I got over 7000 hits); you will find articles by such organizations as Earthwatch, SAIIC, Amazonwatch, and many others. You could contact Survival International, an organization devoted to cultural survival around the world, and express your interest in helping cultures in distress. You could tell others about these web pages so they, too, can learn about cultural survival around the globe. Missions of various types have an interest in helping people make better lives for themselves, although cultural survival is often not their goal (the video titled “Warao Indians of Wakajara, Venezuela” shows the recent life styles of an acculturated, land-based Warao group, as they interact with Protestant missionaries; NO LONGER AVAILABLE).

Warao Audio Examples used in this essay (the CD that accompanies the book, Music of the Warao, includes 24 audio examples of Warao traditional music)

1-1 – Lullaby sung by a mother

1-2 – Lullaby sung by a grandfather

1-3 – Two men playing muhusemoi deer bone flutes

1-4 – Nahanamu harvest festival music

1-5 – Song accompanied by ehuru drum

NOT INCLUDED (available on CD that accompanies book)

1-6 – Wisiratu shamanistic curing song with hebu mataru rattle

1-7 – Wisiratu shamanistic curing ritual

1-8 – Hoarotu inflicting song to destroy tape recorders

NOT INCLUDED (available on CD that accompanies book)

1-9 – Hoarotu curing ritual performed by three shamans

Glossary

bahana – Warao harmful spiritual essence that pertains to illnesses from the eastern cosmic realm and cured by the bahanarotu shaman.

bahanarotu – “Owner of bahana,” the Warao shaman who pertains to the eastern cosmic realm.

ehuru – Double-headed membranophone made from wood; covered with howler monkey skin; played with one stick.

hebu – Warao word for “spirit,” usually an ancestor spirit which can cause illness and death.

hebu mataro – “Spirit calabash,” the Warao sacred rattle of the wisiratu.

Hoa – Warao harmful spiritual essence that pertains to illnesses from the western cosmic realm and cured by the hoarotu shaman. It is capitalized here to differentiate it from another type of curing song written as “hoa.”

hoarotu – “Owner of Hoa,” the Warao shaman who pertains to the western cosmic realm.

muhusemoi – Vertical flute with three finger holes and wide notch mouthpiece, made from the tibia (shin bone) of a deer.

sekeseke – A Warao handmade violin that is often a copy of a European violin (four strings). It literally means “scratch scratch.”

wisi – Warao word for “poison,” referring to the harmful spiritual essence that pertains to illnesses from the upper cosmic realm and cured by the wisiratu shaman.

wisiratu – “Owner of wisi,” the Warao shaman who pertains to the upper cosmic realm. Sometimes he is called hebu-arotu, or owner of hebu.

Bibliography

Briggs, Charles L. 1993. “Personal Sentiments and Polyphonic Voices in Warao Women’s Ritual Wailing: Music and Poetics in a Critical and Collective Discourse.” American Anthropologist 95/4:929-957.

Olsen, Dale A. 1981. “Symbol and Function in South American Indian Music.” In Musics of Many Cultures: An Introduction, Elizabeth May, ed., 363-385. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Olsen, Dale A. 1996. Music of the Warao of Venezuela: Song People of the Rain Forest. Gainesville: University Press of Florida.

Olsen, Dale A. 1998. “Warao.” The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Vol. 2. South America, Mexico, Central America, and the Caribbean. Dale A. Olsen and Daniel E. Sheehy, eds., 188-198. New York: Garland Publishing.

Olsen, Dale A. 1998. “Warao.” The Garland Handbook of Latin American Music. Dale A. Olsen and Daniel E. Sheehy, eds. New York: Garland Publishing.

Olsen, Dale A. 2008. “Cosmic Diplomacy and Celestial Battles: Shamanism, Music, and Healing in Two Contrasting South American Cultural Areas.” In Oxford Handbook of Medical Ethnomusicology, Benjamin Koen, ed., 331-360. New York and London: Oxford University Press.

Discography

Olsen, Dale A. 1996. Music of the Warao of Venezuela: Song People of the Rain Forest. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. Compact Disc that accompanies book.

Filmography / Videography

The Warao. A 16 mm film (and video) by Jorge Preloran. Distributed by University of California, Los Angeles.

With this statement, the author grants public permission to quote from these materials and use the audio excerpts for non-profit educational purposes only. As with proper documentation usage of any publication, credit to the author and the source must be given. However, use for commercial purposes is prohibited without the prior written permission from the author.

Questions, discussion, or more information? Send email to dolsenmusic@gmail.com